Personal texts

The 1950s and 1960s

The following notes were taken from my old notebooks. Between the pages of drafts for artworks, there are texts in which I quickly jotted down thoughts on some of my favourite themes. Here are a few excerpts, some of which include specific dates, when events of particular interest occurred.

Paris is a cemetery of painters.

Yet the myth has fallen from its pedestal despite them. America was discovered long ago.

There is no Europe to rediscover.

The Conquistadors died with their beards.

In the pockets of museum directors, art critics, gallery owners, there is no more room for revolution.

The people’s eyes are used to unexpected events and scandal.

Everything is permitted.

There are no more surprises.

Everything c an be accepted, explained, and understood. Folly has its limits.

The slightest twitch of the smallest muscle can result in a work of art.

A shirt inside-out, framed or unframed, in an art gallery or a dry cleaner’s, is valid.

Everything is good.

This dead and decaying leaf, however, carries the expression of its own existence.

The most profound thought leads to the most passive thoughtlessness.

There is no astonishment.

We can see amazing paintings.

We are surrounded by paintings.

This demolished wall is a painting.

That dirty window is a painting.

This plane motor is a painting.

That slowing wheel is a painting.

The components of abstraction bear their dissolution right down to traces made by ants.

Breaking all norms and barriers, the components of abstraction invade every visible panorama, even paintings. Abstraction surrounds us, envelops us, penetrates us, enters into us through our eyes, and reemerges. Abstraction is transformed into words; it is thought and the denial of thought.

Everything is good, everything is here, everything can be explained, everything can be understood.

Nothing is surprising anymore. There is no more revolution. Painting spreads.

Everything has a meaning.

We should be in awe of these holes in the pavement; this drain is fantastic, and this little bit of dirty paper is

as beautiful as if it were pure white, just like this photo of the outside of a brain.

Abstraction has smashed ideals.

Beauty has snapped the mooring lines.

Venus and Apollo feel awkward about having to rub shoulders with stains.

And they don’t have the right to protest.

It’s another age.

An age that levels hierarchies.

An age that allows everything.

An age that puts aside its surprise.

Perhaps an age that contains the seed of a new newness. The new has never adorned the ancient.

One negation plus another negation and newness arises. Thought about thought that denies thought.

Art formel + tachisme = zero.

Art formel - formalism = Mathieu, academic fireman. Tachisme and constructivism can hold hands. Resurrection and constructivism is a dream

held by old people or utopians.

Continuing tachisme or art informel is the appropriate ambition for those who are starting to feel old.

And then what happens?

Is there not even one window to open?

Or just one path to take?

Nothing to discover?

Not the slightest possibility for revolt?

Not the slightest possibility for divergence?

There is nothing else to try?

Days will continue to go by with their periodic salons, daily exhibitions, art columns?

Everything seems to say yes.

Those with a well-ordered digestive system will oppose any new changes. The established order is satisfied the way it is.

On the ground things weigh heavily and the panorama thickens.

Brightness helps, as does a steadfastness made of steel, and a breach is created.

Just a brief moment to remove our hat and send our regards. We exist and our work starts to exist.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, 1959.

The path of progress is littered with small chapters. We know this.

And there comes a time when we no longer want to know anything.

Centuries of knowledge.

Centuries of errors.

Centuries of success.

A futile weight on our shoulders. The immeasurable to be discovered. A phantom of our fear.

A justification for the passing years.

A single-minded obstinacy, the product of this age. And we march on.

There can be no turning back.

The tempo does not exist.

Only our march exists.

Only the path – our respective path – exists. Written commitment.

Spoken commitment.

Silent commitment.

Flexibility within the norm.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, 1959.

The idea of space in painting can only have a fictive reality.

Until now, all the theoretical speculation on space in painting was only alleged attempts to transform a truly plane surface into its opposite: space.

As the true medium of space is lacking, paintings, in their attempts to portray it, have only given an illusion of space by representing it through its more or less apparent signs; perspective, depth, volume, or through its more intrinsic laws: field, figure, spatial dynamics.

Equipo 57: division of the surface of a painting by a system that orders and develops shapes while totally avoiding the creation of fields and figures and while valorizing the surface divided into one single, homo- geneous plane.

To talk about space with respect to painting is to be mistaken in its appreciation. Painting is a surface. And the history of painting is the treatment of this surface or the way in which it has been used.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, 1959.

It is only by re-examining reality from scratch and taking stock of its limitations that we might, beyond any prejudice, establish the foundations of a simply objective, real, and absolutely non-theoretical painting.

While to eliminate prejudice we need clear theori- zation. To create the objective artwork, on the other hand, we have no need of theory.

What is, is. A painting is a painting. A theory is a theory.

There is no point in demonstrating theories via painting, let alone supporting a painting via theory.

In fact, it is objectivity that matters. And you cannot disrupt realities without risk of finding yourself a bearer of the futile burdens that artists have been lugging for centuries.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, 1959.

t is time to clearly define the bases on which we can construct a new perspective on the fine arts.

Firstly, we must showcase its real foundations as accurately as possible. Not just the physical support in itself, but all that this ‘support’ assumes.

The terms of the reality of plastic research must be clearly defined and to their fullest extent.

The objective reality very clearly defines for itself the terrain on which we can make progress, provided of course that we do not radically disturb, supplant, mystify, deform, or denigrate its components.

Plastic research can be a bona fide fact that takes place within a simple and ordinary reality, like the rest of human activity.

Super-mystification, metaphysics, and extreme theori- zation have led fine art into a situation of privilege and incomprehension, full of confusion and obscurantism, in which mystery, magic, enchantment, and all kinds of subjective values reign.

The great revolution must not be directed against tachisme but against pedantic formal or constructivist painting, against Gestalt-theory, against the theory of form.

Everything that tends to perpetuate what has been a permanent value, a historical value, hampering and eventually halting evolution.

Today is a new day. 1960 brings an entire reality that is prodigiously rich and diverse, full of similarities and contradictions. And it is in this reality that we must find our place, as the humble workers of plastic research.

Observing and ordering (arranging) plastic ideas with the simplicity and diligence that any good worker puts into their work.

No more ivory towers. It is pointless to identify us with the curse of incomprehension.

With this desire for clarity and comprehension, we establish, in their rightful place, all of the real elements of the art world.

Reality shapes us. We can shape reality. Metaphysical or subjective artworks have no place within reality.

The components of plastic research can be clear, precise, and objective like digits, like the materials used. Hackneyed theories and theories that are no more than theories (like the theory of non-theory) have no place in research based on work that objectifies by transforming ideas into realities.

In the field of the fine arts, there is no turning back.

There are some extremisms due to returns to the past that produce new situations.

Museum art must stay in the museums. Cézanne’s phrase: ‘to make art as durable as the art of the mu- seums’ must remain in the history books.

A transformation, an evolution, a revolution cannot come from nowhere and that is why any attempt to change implicitly bears all of the characteristics of what it is attempting to escape. We can only have a clear conscience of what we are claiming to do, of possibilities and restrictions, while accepting partial progressions and understanding delays and setbacks.

Time, in art, strikes me as another formidable sub- terfuge for dissimulating impossibilities.

Time is the essential element in which we evolve (we pass), in which everything evolves (passes), human beings, oil paintings, sculpture, music, civilizations, relationships, revolutions . . .

Theorizing art involves an impotence that is disres- pectful of the art world and constitutes an abuse of people’s credulity.

Apparently, time genuinely intervenes in the expe- rience of a work of art. Its observation and the pleasure that it can elicit require a certain attention span. But this time is not the material element that the artist has used, by working on the surface or in the space. Time as a working element escapes its real possibilities. When they must modulate a tempo, musicians do so by determining its dimension and configuration within their piece.

Julio Le Parc, 21 June 1960.

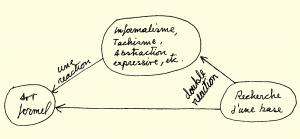

Our position, a very simple outline:

Yesterday:

Constructivist painting based on the theory of form, producing paintings with the free interpretations of painters and freedom in composition.

Yesterday and even today:

Informal painting, tachisme, and all kinds of abstract expressionism freeing painters from geometric for- malism, yet subjecting them to all kinds of expressive formalism to arrive at the summit of appreciation, where everything, absolutely everything, has a an artistic value.

Today and tomorrow:

A new attempt at clarification. The time to establish the first permanent feature upon which plastic art can develop on solid foundations: free of all extra-plastic constraints, any idealistic, philosophical formulation, all subjectivity, and all extreme irrationalism or rationalism.

Our refusal:

First of all: the worship of form (constructivism, formal painting, neoplasticism, etc.). Secondly: abstract expres- sionism of any kind (informalism, tachisme, lyricism, abstract surrealism, truculentism, amorphism, etc.)

Our forebears:

All efforts made to seek clarity in plastic arts, including Mondrian, Albers, Max Bill, and Vasarely.

Points to consider for a manifesto:

• Optical movement

• Psychology of vision

• Psychology of form

• New studies in experimental psychology

• Real movement

• Visual, optical, or eye movement

• Ocular psychology

• 9° focal vision

• Peripheral vision

• Uncontrollable optical stimuli in the peripheral region

• Sequential stimuli

• Unstable structures at the periphery versus sharp, clear structures in the focal vision

• Changes in meaning according to whether the vision is peripheral or focal

• Works with forms: preeminence and particular meaning of the form

• Works with the relationship between forms: neutrality of forms, freedom to link them (Mondrian: different relationships with different meanings)

• Works with groups created by unique forms with a single type of relationship (Vasarely), introduction of free variants that break the homogeneity, creating an alternation in the visual reading of the surface

• Works with progressions: treatment of a homogeneous surface with neutral shapes (squares, circles, etc.) so that it changes rationally owing to quantitative progressions caused by changes in ambivalent directions

• Creation of unstable structures in the peripheral vision that force the eye to shift the focal vision in order to capture the structures that are not produced in that focal area

• Systematizing changes or evolutions of a form into homogeneous groups without breaking the logic of homogeneity

Changes through:

• progressions

• ambivalent progressions (horizontal, vertical, diagonal)

Metamorphosis of:

• growth

• reduction

• transformation

• appearance

• disappearance

• rotation

• transference

• speed of transference

• shape

• colour

• tonality

Points of departure:

• a shape

• a series (in which the chosen shape creates a movement or a sum)

• a group (within which the series multiplies through movements of series or quantitative additions, or the unstable structures that result from the relations between the shapes, series, and groups, creating an optical motion produced by the unstable structures relative to the shapes, series, and group)

• a group of groups (in which a given group may inter- vene in another group, or two or three intersecting, ambivalent, or additive).

In this last case, even more than in the preceding one, the problem of the relations qua matter on which one work is taken to another state of evolution; therefore, it tends to create groups in which the idea of the shape that comprises them, the idea of the series that gives them structure, the idea of the group that creates the optical motion, remains on a totally intelligible plane. This leads to a true relationship between these elements, freeing to an even greater degree the play of focal vision and creating unstable structures within the peripheral vision.

With this minimum of artistic/aesthetic interest, peripheral stimuli take over, to the point of forcing the eye to constantly move over the surface in order to sustain the ungraspable elements that disappear within the focal vision.

Additional points to consider:

• Field and figure (Malevich)

• Field and figure, figure and field (Vasarely/Arp)

• Instability of attention (Albers)

• Vibration in black and white (Vasarely)

• After-image

• Real movement/time (Nicolas Schöffer)

• Three dimensions. Many visual angles.

• Colour

• Colour/light

• Graduated depth

• Two planes

• Two planes or more

• Superposition of shapes and colours

• Real movement of shapes and colours and their optical relationship

• Time

• Temporal programme

• Multiple atemporal programmes

• Programmed movement

• Movement of changes

• Constant changes

• Alternate changes

• Mobiles, free movement

• Limitations on free movement

Historical movement, very simple schema: of the sum of values, elements, stimuli that predominate in classical painting, confused accumulation of all sorts of calls to the viewer’s visual, emotional, and rational understanding, including the well-known stages of classification of contemporary painting (expressionism, cubism, constructivism).

Eventually work with the simplest physical ele- ments, those that allow us to understand the psy- chological mechanism of optical motion and its early relationships with the spirit, in order to conquer, step by step, consciously, the other sensorial and mental mechanisms and at last configure the visual elements in accordance with the knowledge that is established through the type of relationship between the human eye and the human being.

Plastic arts: logical point of departure, vision.

Julio Le Parc, July 22, 1960.

The type of research we are carrying out requires a new type of relationship between us and a new type of research, where the individual becomes part of the collective.

Julio Le Parc, 23 juillet 1960.

In 1941 Mondrian pointed out that: ‘One must consider that in art, the culture of particular form has peaked and come to an end, and that art has undertaken the culture of pure relationships. This implies that the particular form, freed of its limitations and reduced to a more neutral [form], can now establish purer relationships.’

Paraphrasing him, nineteen years later, one could say that: ‘One must consider that in art, the culture of particular relationships has peaked and come to an end, and that art has undertaken the culture of pure relationships. This implies that the particular relation- ship, freed of its limitations and reduced to a more neutral relationship, can now establish relationships that are purer.’

This articulates a new phase of evolution. Mondrian, clearly denoting the end of the culture of particular forms and consciously striking out towards the culture of relationships, creates a standard, that is: particular relationships. His contribution is extraordinary and surmountable.

It is now up to us, in the midst of the confusing contemporary art situation, to clearly and fairly esta- blish standards that will carry on the idea of purification that had Mondrian working with such perspicacity and conviction.

Therefore, undoubtedly by opposing all formal art that Mondrian opposed, and also opposing Mondrian’s art when it is static and definitive, and the sequels of his false followers, and essentially by opposing his support of neutral forms through particular relationships, that is, to valuing the relationships of the forms over the forms themselves while maintaining different kinds of freely chosen particular relationships, we in turn maintain that in the clear and conscious development of art, the culture of forms culminated with Mondrian and that now the culture of relationships that he articulately imagined has also, in its specific nature, culminated.

Thus a culture begins in which the particular form is decisively discarded and the particular relationships overcome, and a culture is developed in which the relationship acquires a new standard on its way to independence and purity and in which the forms are a completely neutral support with no power in and of themselves, and their relationships would respond to a total and unique nature that would completely determine the meaning of the work.

Julio Le Parc, July 29, 1960.

Why did Max Bill introduce Mathieu, Dubuffet, and other tachistes into the Art Concret exhibition in Zurich? Further to any reasons that Max Bill may raise, for our part, we have drawn our own conclusions regarding the presence of Mathieu and co. in this exhibition. It is, in fact, not so aberrant as one might think, since fundamentally, the attitude of these painters is in no way different to those of many others exhibited here who claim to conceal their improvisations under geometric forms. This exhibition has brought together contradictions into a consensual, regressive, academic, and formal viewpoint.

Julio Le Parc, 29 July 1960.

With regard to incorrect declarations that claim to make definitive classifications based on the physical material with which we make our works, it must be pointed out that this attitude is obsolete. Progress has never been measured in relation to physical media but on the originality of the content. Even though there is a very close connection between materials and fabrication,

it is the result that counts. And what remains inscribed in art history are the ideas applied to materials that enable them to be visualized.

To claim today that easel painting has had its day is a completely childish and extreme point of view that indicates a total ignorance of plastic problems. Easel painting is one of the outcomes of treatment of a surface. To put things into perspective, let us first of all consider the role that the surface plays, or can play, or no longer plays as a two-dimensional physical medium, in the context of resolving today’s plastic issues. Having done this, we will only have made one step towards understanding the real issue of plasticity, which is located outside any physical medium that may bring solutions. A spirit of originality is a new way of conceiving, thinking, and feeling the characteristics and constants that are themselves defined and acquire a reality as they become visible on their physical media, which are themselves conditioned by this new spirit. By ‘physical media’, we mean not only the material with which we are working, but also any graphic, visual, or theoretical concept that gradually forms it. All too often we observe the disappointed pretensions of false inno- vators, full of retrograde and inevitably passive ideas, using technologically modern materials or, just the opposite, salvaged materials. Because of this incorrect view of things, they base their work on the theoretical worth of their artworks, a theory upheld by the artificial conditions of fabrication, devoid of all substance.

Julio Le Parc, 29 July 1960.

An Attempt to Evaluate Our Research

We should specify that there is nothing absolute or definitive about our work.

Our main preoccupation is to situate ourselves within today’s art, while keeping in mind that plastic art should have a social connotation. Having come to the artistic life by the usual means (studying drawing, painting, art history, etc.) and conditioned by the social superstructure that is art, both from a conceptual and emotional point of view (means of expression, drawing, painting, sculpture, individual work) as well as a social one (the teaching of drawing and painting, competitions,

official salons, galleries, art critics), we are aware of our situation and the contradictions that it entails. We have come to realize the depth of the choice before us in the confusion of the current moment. And, in more or less approximate terms, we can see what is at stake in this choice.

Either we can continue in the mythical world of painting, with our greater or lesser capacities of expres- sion and experience, accepting the social situation of the artist as a unique and privileged individual with a predetermined destiny.

Or we can demystify art, reducing it – put very simply – to every other human activity, in which the interest lies in visual phenomena and not in the sudden illumina- tions that we might have from our inspiration and the state of our souls. Otherwise, its expressive value is the product of a profound, intangible identification of the painter/human being with his or her era, and with human aspirations. Faced with such a choice, we are happy to have taken on the task of clearing the path, with the goal of being able to consider art as a simple human activity.

In order to get there, we continually check our task with research done with a clear conscience, for our experiences and our social activity. We would like to eliminate the word ‘art’ from our vocabulary, and all that it currently represents.

We have conducted research, and we propose to continue our research, the results of which could still be compatible with traditional nomenclature such as drawing, painting, relief, sculpture, and even a work of art that can be appreciated and sold in current art terms.

For us, the concept of a work of art is beginning to disappear. We are simply trying to depict human beings’ personal experiences using clear and objective means.

As to how we will achieve this practically, we empha- size an immaterial plane that exists between the work (or the experience) and the human eye. Every work of art is, above all, a visual presence. We recognize the visual dialogue between person and object. The role we give to the existence of the plastic object is neither in the preconceived emotional notion of the person, nor in the technical creation of the work itself, but rather in the combination of person and object in an equidistant visual plane.

Hence our opposition to solutions of formal, syste- matic, random, or any other types of ordering, in that these are simply rhetoric about surfaces, volumes, space, or time.

Let it be clear: our intention is to situate our exper- ience within this immaterial plane between a person and a perfectly malleable object. This explains our distance in relation to form, which is, as Mondrian pointed out in his writings in 1941, in possession of a particular character.

We place ourselves at the centre of the problem of relationships, reducing the form to its simplest expression by representing it in the anonymity of homogenous shapes. We thus give more freedom to the relationships that materialize an invisible element of the work that isolated elements cannot.

By moving to another level, we lay bare the rela- tionships of these specific characteristics, conferring on them degrees of anonymity and homogeneity. We thus liberate ourselves from any attachment to formal values and its extra-visual consequences.

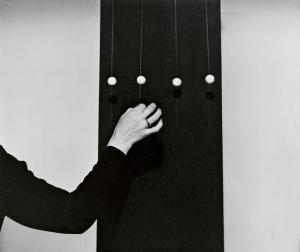

During the course of our research, we have increas- ingly distanced ourselves from the plastic object itself, which has its own solutions, and from its connection – signified ahead of time – with the viewer. We are reaching more immaterial levels where it is possible to establish the coordinates of the visual relationship between person and object in a truly dynamic fashion. We consider movement to be an intrinsic element of visual phenomena. We do not consider it either a problem or an objective. We establish the difference between movement and agitation. If we can establish a dynamic relationship between the human eye and a plastic object in an implicit manner, this will generate an experience of movement with the implication of time. Starting a motor will produce motion, but this is not sufficient to see it as visual research. Being aware that something is moving is not participating in the phenomenon. The use and abuse of movement, like other technical resources in plastic art, hides a lack of comprehension of the sense of movement – if not complete incompetence.

We do not pretend to be able to completely tackle the problem of movement. We only want to point out the validity of the sense of movement based on the dynamic relationship between the viewer and the artistic object.

We thus establish an initial appreciation of movement within a strictly physiological plane. The inevitable relationship of the human eye to certain visual stimuli. The motor of movement that occurs is not only due to the physical makeup of the organ of vision, and rather than present it with easy to comprehend, recognizable representations or forms, I give it a continuous series of stimuli from which escape is impossible. We think that this physiological level is very important. A static surface can contain valid elements, likely to produce movement through a dynamic interrelationship with the human eye. On the other hand, a moving wheel, even with its real-world kinetics, can leave an individual totally indifferent after a first glance.

We examine the development of movement based on physiological observations of human vision. We do not care about movement that is mere agitation. Movement means time, plastic work, and space. We find that bringing them together, based on physiological considerations, goes hand in hand with the characteristics of space, time, and their connection.

Our first observations: a two-dimensional space or a surface can establish a dynamic relationship and visual movement. A three-dimensional space, by means of its multiple viewpoints, determines a time for appreciation. Static objects can count on the viewer’s movement through space. When we arrive at real movement, the relationship with the idea of movement becomes more difficult.

Because real movement, on a surface or within a volume, contains movement at its base. There is a major difference between the idea of movement and actual movement. An object that moves may not comprise the idea of movement, despite its agitation. We realize that the prominence accorded to movement in the visual arts has its own rationale that differentiates it from real movement, even though it refers to it.

Starting from a basis of real movement, the difficulty becomes a problem of time, with the implications of using the characteristics of the idea of time. It is possible to go from free movement to propagating movement, with a beginning, development, and ending, in which, according to a less predetermined plan, several programmes may come into play simultaneously and for which no programme has been worked out beforehand. It is also possible to use approximate systems for situations in which movement engenders an indeterminate time with unpredictable characteristics that can more or less be calculated with a probability system.

Julio Le Parc, 6 November 1960.

l would like to express a fact that I believe is funda- mental to our research. It constantly manifests itself, more or less obviously, in almost all our work.

We have established the artistic fact, on a strictly visual plane, far from its formal content and its expressive poles. We have proposed the annihilation of the parti- cular form because of its rhetoric and individual value.

There is a third element that exists in a void. Its reality is palpable and, at the same time, incorporeal; it is neither drawn nor directly fixed in the matter. It can be captured or transformed, but always on or in relation to other elements. It does not have an existence that is linked to its origin (the white of a white sheet of paper, besides the light/paper relationship, resides in the paper). This third element does not exist on its own, it is the combination of two other elements. It is not a simple relationship. It is the relationship itself, or the relationship to such a degree that its basic elements become practically null, but still remain necessary. l believe that fully understanding this phenomenon will allow us to understand our position better, and carrying out new projects will yield more precise results.

l consider this phenomenon to be closely linked to the idea of time. Not the passing of time, but rather time-existence, time-connection. Therefore, a situation of extreme relativity arises, but with all the attributes of a tangible and permanent reality: the acute existence of nonexistence.

In this situation, where it is impossible to value this element with our perception of reality, since it has no basis of its own, we find ourselves in the strange situation in which this element is nothing but itself, the one that counts, the one that seizes all the attention.

There is something frightening, or heart-warming, about knowing that this presence is so acute; existing through others, while on its own it is absolutely nothing.

If we develop and grow our understanding of this element, unforeseen perspectives will open up.

he use of form, as well as its meaning, falls into the domain of traditional art. By working on it, this element can easily escape us, like water slipping through our fingers. Its existence, based on nonexistence, leads us to another field, not one of the thing itself, and even less of the thing-meaning. It simply leads us beyond, towards a marvellously modular immaterial plane.

Julio Le Parc, 8 March 1961.

By making luminous, moving boxes, I have been able to observe, among other things, simultaneity. A simple visual, static, or mobile plane, with its own life, space, and time, joins up with other, equally independent planes, which all converge into one visual space. In this way a cumulation of planes is achieved. This staggered depth is controlled under the same time period. And what occurs in this visual field is different to that which occurs in each of the planes.

It is futile now to go back and explain why the traditional classifications of visual art (painting, sculpture, etc.) have been surpassed. Limiting each field of creation, they place the object to be contem- plated on one side and the viewer on the other.

First of all, contemporary creations overcome these limitations, seeking to modify the artwork- viewer relationship by asking viewers to participate in new ways.

We therefore find ourselves facing a situation whose complexity is thought-provoking. Its evolution can have obscure aspects to it. It is not a matter of replacing one habit with another. We must draw conclusions and anticipate the next steps clearly, whether these are positive or negative.

Breaking away from traditional norms does not justify confusion or gratuitousness.

The notion of spectacle connected with visual art sets us along one path; while that of the activated or active spectator sets us on another. And both can also become associated.

Through our status as creators, we have a critical imperative with respect to the artworks produced and their connections with the viewer. The total result must be of unquestionable clarity.

The design and creation of the artwork must respond to a clear idea, its visualization must affect the viewers’ perception, and their participation must take place within a timeframe corresponding quali- tatively to the whole.

A great deal of today’s artworks do not hold up under scrutiny. Some valid attitudes are manifested into creations whose novelty only resides in their appearance, in the material used or their manner of presentation. Without analysing them deeply, under this pretence of originality we discover an equivalent art to the kind that they claimed to surpass – that is, when these works don’t merely boil down to a taste for oddity or snobbery.

Without entering into crucial considerations, we can point to a whole series of new artwork-viewer relationships that go beyond mere contemplation, exploring rapports such as the ‘viewer-artwork’, or ‘stimulated-viewer’, ‘moving-viewer’, ‘activated-viewer’, ‘performer-viewer’, and so on.

The role of the artwork and that of the spectator will be modified. Fostering the active participation of an artwork is possibly more important than passive contemplation and can develop natural creative conditions among the audience.

But the extreme pretentiousness of desiring viewer participation can lead to placing them opposite a white canvas on an easel and asking them to make use of a box of oil paints; or to reinventing the typewriter as an artwork requiring the viewer’s active participation to create poetry.

In the same vein, and with a concern for spectacle, using the active-viewer as an object of contemplation (while s/he participates in an artwork, s/he is the object of spectacle) simultaneously presents the existence of a viewer who experiences the creation with the awareness of being observed and a viewer who contemplates it. In the case of the ‘viewer-artwork’, we find a similar situation to the previous one, only s/he is aware of no longer being a viewer, except to contemplate others in their act of contemplation.

And so we arrive at the incorporation of the real action, an action that is no longer individual on the viewer’s part, but entails the interaction of several viewers. On this path, we could devise sculptures to be fought, dances to be painted, paintings from swordplay, etc.

We could even, in this concern for the violent participa- tion of viewers, arrive at non-creation, non-contemplation, or non-action. We could then imagine, for example, a dozen ‘non-action’ viewers plunged into total darkness, immobile, saying nothing. If they could no longer think and perhaps no longer breathe, we would attain the highest degree of a new art. But while remaining within these preoccupations, we can try to find solutions far from the absurd. Because this element of hasty improvisation falls within an entire phase of despair and boredom, if not simply a complete lack of clarity.

The notion of spectacle as related to the visual arts has always had a pejorative sense. By clearly allowing the reversal of the traditional situation of the passive- viewer, we circumvent the idea of spectacle, arriving at the notion of activated or active participation. This concern is closely aligned with the very conception of the artwork, its production and relationship with the viewer. We are clearly distancing ourselves from aesthetic or anti-aesthetic norms, because now, after dozens of years of modern art, we have reached the point where anything can be considered art and simplistic postulates can elude the problem by affirming that sleeping is an art; this elevation to the category of art of the things and facts of everyday life harbours the intrinsic contra- diction of wanting on the one hand to deny works of art altogether and on the other, while maintaining values, transforming everything into art, with the commercial aspect also having a hand in this state of affairs.

To the conception-creation-visualization-perception circuit another phase is added that governs the whole ‘modification’ aspect. This idea leads us to the notion of instability. The notion of instability in visual art responds to the condition of instability of reality. We try to manifest it in creations that faithfully express it in terms of its fundamental characteristics.

We observe its parallel development in the reversal of the viewers’ contemplative situation in favour of their active participation.

We could even establish degrees of this evolution.

For instance, Kinetic Artworks on the surface (paintings) strive to place viewers within a real relationship wherein their participation, strictly by way of visual solicitation, engages them within a perceptive tempo in which the physiology of vision is the primary concern. The artworks that best succeed at this are those whose creation distances itself from the notion of recognizable forms with a particular character and whose free relations lend themselves to a particular interpretation. These artworks develop an idea that is manifested on a homo- genous surface in which the forms used all respond to the same point of departure (if they are not all equal); their positioning within the plane responds to the same idea that gives to all of the relationships equivalent homogeneity to that of forms.

These ensembles are capable of creating unstable structures perceived within the peripheral field of vision, creating an indefinite period of perception in which the physiologically activated viewer experiences the unstable artwork.

In the case of Kinetic Artworks in volumes – those that are created through the viewers’ displacement – they truly have value when the viewer’s total perception, as they move, responds to the same data sets of their design and creation.

The value of this perception resides, not in the capricious addition of the various points of view – each of them potentially being the equivalent of a traditional, static painting – but in the close relationship of displacement between the viewer and the multiple visual situations arising as a result. Since each one in itself has only minimal value, the most important element is a third state produced by the displacement. The most remarkable artworks on this path are those that include the notion of acceleration that produces a genuine sense of movement, since the slightest displacement of the viewer produces a visual movement several times superior to the actual movement of the displacement. This visual movement is subject to permanent characteristics.

These artworks lead us to the kind that are created progressively as we look at them. Here, the act of ‘experiencing’ the artwork attains another level, since the viewer is experiencing the artwork in real time. The specific movement of their perception manifests a measure of time (a duration) in which the artwork is created within them. The notion of beginning and end are thus swept aside, as are notions of the stable and finite character of traditional artworks: these are non-definitive, mobile artworks offering multiple situ- ations and constant variations. In order to manifest instability in its most abstract sense, these artworks must remove solicitations from the viewer as much as possible, stemming either from formal variations or special meanings. The very nature of their design and creation aims (in a way that is foreseeable, to an extent) to bring about the effects that will occur within the viewers’ perception. Viewers wholly participate in the indeterminate data set and it is their perception that will give them a particular image of the artwork.

In the artworks that we have just analysed, we might say that the viewer has been ‘activated’: his or her activation is fundamental to the reality of the artwork.

Actual participation (manipulation of elements) presents us, however, with viewers that recreate the convertible artworks submitted to them.

Obviously, the result can have several meanings. It is based, on the one hand, on the real and combined participation of the creator and the viewer; and on the other, on the conception of the artwork presented. If the data of the convertible artwork responds to the principles of traditional art (varied forms and free arrangement) the viewer is predestined to indefinitely recompose, within the same artwork, a multitude of passively contemplated artworks. In this case, the author of the artwork might describe themselves as a creator of convertible artworks, but what escapes them is the visual outcome of their artwork, which will always be – despite any amount of modifications – stable, traditional, and passively contemplated. From these observations regarding the active viewer emanates the possibility of developing their natural creative condi- tions as well as the danger of orientating towards the creation of artworks of a traditional nature, without excluding the possibility that this viewer, by creating personal artworks, later manages in turn to create artworks involving viewer participation. However, the viewer’s active participation is valid within a framework in which all states of the phenomenon, manipulations and visual perception, respond to an unpredictable process that nevertheless falls within an overarching context governing the artwork (conception, creation, modifications).

From the design perspective, the notion of program- ming (often used in the New Tendency) encompasses the manner of devising, creating, and presenting unstable works of art. It is a matter of planning in advance all the conditions of development of the artwork, clearly determining its terms so as to allow it to be created within space and time, subject to a given set of deter- minate or indeterminate contingencies deriving from the environment in which they take place and from the activated or active participation of the viewer. A mul- titude of similar aspects will result from this and the viewer will grasp a portion of them, always including sufficient visualizations for the unstable whole to be perceived.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, September 1962.

Position of the undersigned regarding the New Tendency

1. Raising the alarm.

As with any artistic movement, organized or not, the New Tendency is running the risk of turning into a new form of academicism. We are seeing a large proportion of the artworks it produces going no further than the object itself, with artistic intention and a lingering over aspects of precision, care, and even attractiveness in the artworks (luxury handicrafts). This interest, which focuses on the object itself, fails to remain open to other situations in which the viewer can better participate.

Producing a series of experiments that have mater- ialized as works is valuable as an approach for creating different relationships with the viewer. The weakening of this intention and a focus on formulaic approaches (uniformity, movement, plays of light, etc.) results in an apparent evolution, but actually moves away from the original concerns. It becomes affected, a form of academicism.

In the New Tendency’s current state, anyone within the movement or outside it, with only a few of today’s tools and materials, can produce an artwork that is scarcely different to any other. And so, within the New Tendency movement, one can develop a ‘creative’ personality just like the earlier New Tendency; by changing the colours of the palette, anyone can become an impressionist painter. In this way, with a smattering of ‘public relations’, a bit of luck and work, one can aspire to rise through the artistic ranks in search of personal success. These dangers are intrinsic to the New Tendency. It harbours its own contradictions.

2. For the New Tendency to continue, we feel that two attitudes are required:

• a) A critical approach in order to combat this incli- nation to academicism. We are more or less aware of the negative aspects: gratuitous sequencing of elements to ensure they are free or regular, unjustified choice of materials, undue focus on attractiveness, the artist/work-of-art relationship, etc.

Critical, and even selective analysis meetings should be organized within the New Tendency, based on the general understanding of New Tendency artistic production, on works presented at the Louvre, and on presentations of ideas of components.

• b) An open-minded attitude in order to allow other avenues for relationships with external parties and the viewer. We should be moving towards an action that is more combative, more detached, and less fearful of external parties, looking to other possible activities and other ways of expressing ourselves. We should not settle for being the isolated or associated producer of objects that will be used to replace sculpture or painting, or to fit in with architecture, decoration, marketing, etc.

The undersigned support this position and put it forward to the New Tendency. They further propose:

• - A New Tendency manifesto,

• - Analytical graphics of New Tendency artworks,

• - Some basic organization,

• - A series of acts ancillary to the New Tendency exhibition at the Louvre.

Julio Le Parc, text written on the occasion of the Nouvelle Tendance exhibition in Paris, 1964.

As of this day, we the undersigned declare the foundation of the Anti-Nouvelle Tendance Anti-Visual Anti-Art Anti-Research Anti-Group (known as N.E.A.N.T. [Nothingness]).

This group is unlimited.

Everyone is included.

It will develop among its membership a mistrust of all forms of art.

Obviously, it will not reveal the tricks of artists, critics, etc. It will not state, for example, that the Nouvelle Tendance exhibition at the Louvre, which consists of craftsmen of luxury goods, would like to become a new academicism and establish new mannerisms. It will not point out the disturbing sight of an entire legion of do-it-yourselfers equipping themselves with power drills, saws, electric cables, and so on, just because moving lights have become fashionable.

In the same way that we see another large group, perhaps even a bit larger, scouring marketplaces and flea markets, tearing down posters, rummaging in garbage cans – all because tachisme and informal art are dead, and because in New York they’re buying pop art.

No, we will not criticize.

The meaning of the fierce struggle – manifested by current groups and those from before (Master Dadaism) – is outdated, a frozen and repetitive attitude, academia.

Without necessarily submitting to it, we must admit that art and its band of cohorts is an evil like so many other evils that afflict or numb humankind.

It can only make us smile, Nouvelle Tendance’s so- called common sense. With its robust intention to allow art to progress, to occur in all situations. We replace one habit by another. Instead of hanging paintings in the Louvre, we are now hanging boxes, lights, wooden reliefs, etc., with the declared (or undeclared) pretention of invading decoration, advertising, galleries, archi- tecture, etc. Among official or non-official supporters, the gregarious spirit of banding together becomes a trend given to groups or teams, either at the Paris Biennale, that of San Marino, or at the International Congress of Art Critics in Rimini.

Anyone can form a small or large group of two or six members and even start an international movement.

In light of this general drive (after informalism) to save art either by returning to figuration, or by wanting to instigate new realism or Pop Art, or a visual-centric art, all we can do is pose a major question and, before continuing or including ourselves in any of these move- ments (or perhaps all of them at once), leap into the void.

Obviously, our Anti-Group (N.E.A.N.T.) has no pro- gramme, nor precise (or imprecise) goal.

We will embark on our real or imaginary plan with no intention whatsoever to make a statement.

For example, instead of forever wanting to change art and the creation of so-called works of art, we will carry out an entire series of tests to stimulate people a tiny bit. We propose, for example, going to see the N.T. exhibition at the Louvre with closed eyes, or covered with a black bag, or white, whichever. At the Louvre, or in the street, or at the Sorbonne, we will hand out inflated balloons that can be popped. We will hand out whistles at the Louvre, or elsewhere, so that viewers can – faced with the admiration, repulsion, or indifference that the spectacle inspires – give a blast with their whistles. We will encourage them to use flashlights to light up the luminous New Tendency works on display at the Louvre.

We will recommend, still within the framework of the New Tendency at the Louvre, that children (and adults, why not?) visit the exhibition on roller skates. We will suggest that they go to a certain security guard at the Pavillon Marsan, or to a salesperson at a stationery store on the Boulevard Saint-Germain who is known for his bad temper, and wear out their already thin patience with requests for information. On the occasion of the N.T. exhibition at the Louvre, we will hand out sheets of white paper at the entrance, so that visitors can ex- press all the bad things they like about this show. And, at the exit, we will hand out more sheets of paper that can be torn into a million pieces, since the guards will prevent N.T. works (and others) from being destroyed (this substitution is provisional, until people have the courage to destroy everything).

Then, we will organize, in a hall in the centre of the city, a training session for increasing people’s percep- tive capacity, by administering a shot of mescaline to all candidates.

In the same way, through a rigorous selection process, we will choose a work that is characteristic of each avant-garde trend (pop art, new figuration, new realism, op art), which will be publicly burned on the Place de l’Opéra. We will continue our efforts towards children and young people.

As a preventive measure, we will offer them a series of anti-educational, anti-formative situations, with the agreement of the Minister of Education, Youth, and Sports, and the directors of France’s cultural centres. Failing this, infiltration or sessions held in vacant lots. Before arriving at the stage of collective suicide, we will try nonetheless to leave our ‘mark’; we will set up a collective avant-garde art studio, and we will design the ‘masterpiece’ of the era. We will create a major summary statement. To this end, we will take a major work by Tintoretto from the Louvre, add a few extra brushstrokes to it, we will deform and modernize the faces, preferably making them shout; for women, we will stick on real brassieres stuffed with straw, here and there we will dress figures up in dirty clothes, others will be covered with plaster, etc. In certain places, we will put, on transparent plexiglass plates, small circles and squares, patterns, mirrors, mobiles, etc.

All of this is contextualized with throbbing motors.

In the shade and with colour projectors and rotating grids, a few levers and buttons so that spectators can activate them. A bit of noise and the masterpiece will be complete.

Then we will make a life-size reproduction of it for all the museums on the planet. A family-size repro- duction for every home. A miniature reproduction (pocket edition) for travelling. Of course, there will be other editions: gingerbread ones for food lovers, liquid versions, flexible versions, etc. This work will lend itself perfectly to the integration of the arts, because it can be ‘integrated’ into architecture, with a few changes in colour, size, lighting, etc.

Completely red for a house of vice, all in blue for a convent, for example. Very narrow for a tower, large and circular for a theatre, round for car wheels. Thus industrial aestheticism will have no cause to envy art. Semantics and the theory of information will plumb the riches of this work, which will lend itself to numerous tests, and so on.

With all that we have just proposed, one could suppose that we have a programme after all. lt’s nothing of the kind, because we permanently drift and commit ourselves to nothing. Things will not happen. There is no programme, and it belongs to everyone.

Julio Le Parc, April 1964.

Signature authorized on behalf of everyone: ... The “only one” (alias Le Parc). An ironic text that received no response, reflecting a degree of disappointment on my part with respect to Nouvelle Tendance.