The GRAV

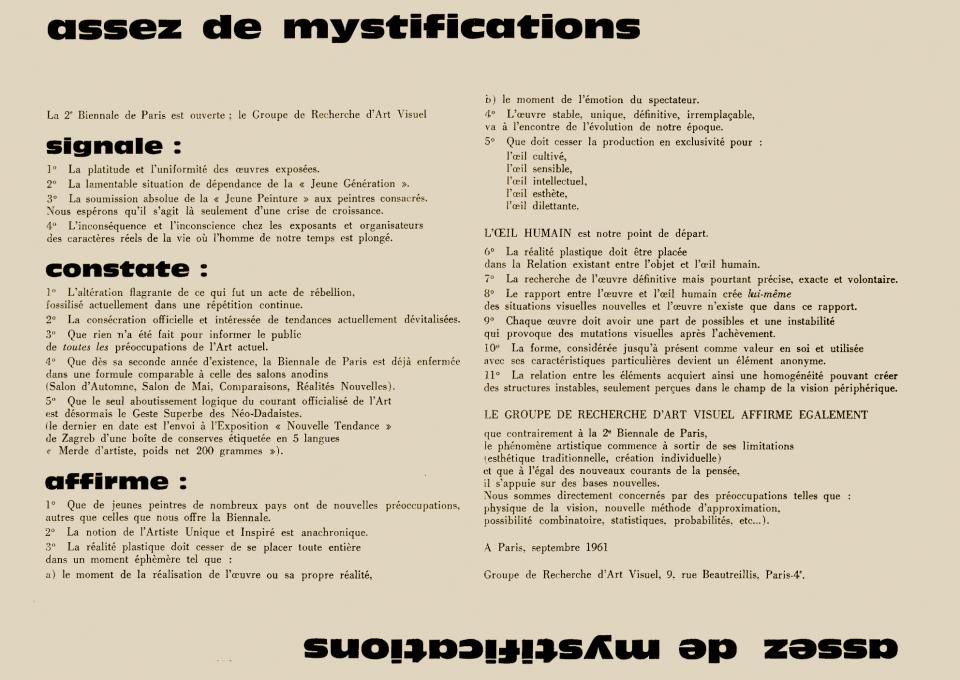

In 1960, I actively participated in forming the GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel). I was an active member up until its dissolution in 1968. I therefore took part in all of its analyses and all of its directives, its collective texts, interventions, and artworks. A large part of my thinking and production was connected to the GRAV throughout the group’s existence.

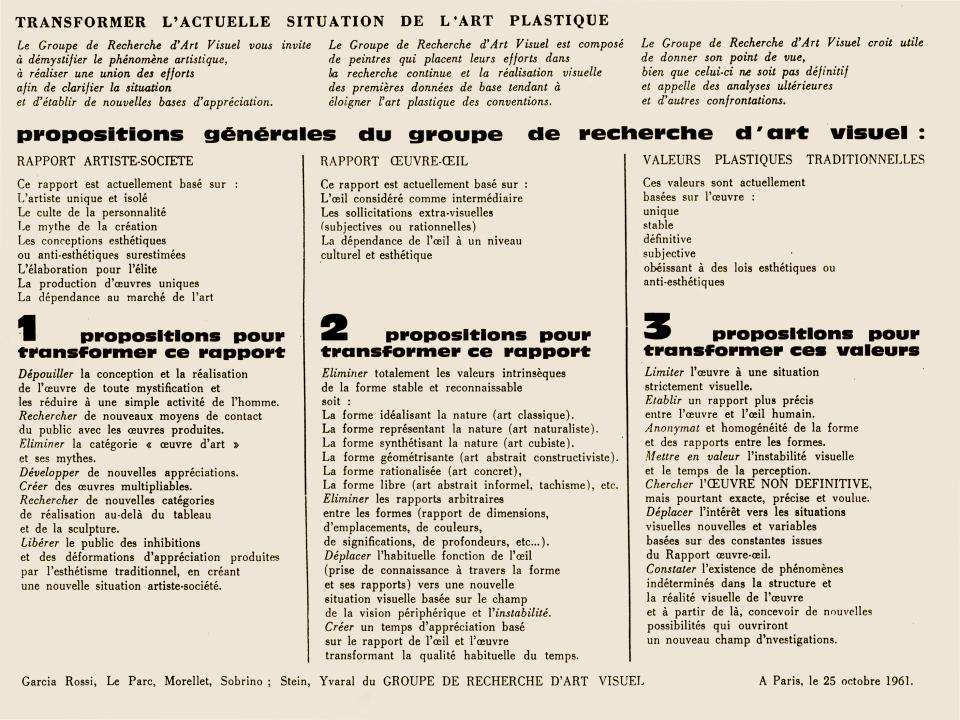

In July 1960, several painters, who all had once had traditional artistic attitudes, decided to create the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, where they could compare their research and bring their activities together. Their goal was to escape current trends in the art world – culminating in the figure of the lone painter – and attempt, through group work, to clarify various aspects of visual art.

We would like to remove the word ‘art’ from our vocabulary and all that it currently represents.

We prefer to consider artistic phenomenon in terms of a strictly visual, non-emotional experience located in the plane of physiological perception.

Our experiments may retain a traditional form, such as painting, sculpture, and reliefs. However, we do not situate plastic reality in the creation or in emotion, but in the constant relationship that exists between the plastic object and the human eye.

We have examined the problem of movement from a number of angles. We will list several elements as examples, but we will not give the history of this evolution here.

1. Surface movement:

• a) The representation of movement (a large part of traditional painting, cubism, futurism);

• b) The concept of movement in formal art (Mondrian, Delaunay, Max Bill, etc.);

• c) Movement whose basis is the physiology of vision virtual movement (optical) (Albers, Vasarely, etc.).

2. Static reliefs:

• a) Optical movement (Tomasello, etc.);

• b) Movement obtained by the movement of the viewer (Vasarely, Soto, Agam).

3. Surface movement:

• Animation of a surface that creates a new optical experience (Duchamp's rotoreliefs).

4. Surface-screen:

• a) Cinema (filters, scratchings, film stock, animation);

• b) Light projections (Schoffer, etc.).

5. Reliefs in motion:

• a) Mechanically driven (Tinguely, etc.);

• b) Natural movement.

6. Spatial construction in motion:

• a) Mechanically driven (Schoffer, etc.);

• b) Natural movement (Calder, etc.).

(Several of these aspects have been developed by the group members. The painters listed here are mentioned in order to illustrate our classification, the list is not exhaustive and has no other meaning.)

The idea of movement presupposes the idea of time. When it moves, the plastic object leaves the spatial plane for a spatiotemporal plane.

The perception of these phenomena is displaced, and we can thus establish an image-movement-time relationship.

Nevertheless, movement can be seen from two different viewpoints:

• 1. Gratuitous agitation.

• 2. Development that creates a new visual situation.

In the case of the former, the goal of animating the object is the object-spectacle, and the results are essentially emotional in nature.

The image-movement-time relationship can be altered, creating an image in which movement is given excessive priority.

The animated object-spectacle has always existed. But the fact of making a given sculpture rotate only implies the incorporation of movement into a given static situation.

What do we mean by movement?

The three factors of image-movement-time must be incorporated in a whole, whose components cannot be dissociated. Their connection will be constant, and a new unity with its own existence will appear in the visual field.

Nevertheless, we are not concerned with this unit as a plastic object. Only the existence of the object-eye connection is of interest to us.

How is this connection defined?

• 1. On a surface or fixed relief:

• The form, which up to now has been considered as a value in itself, and used with its specific characteristics, becomes an anonymous element distributed across the surface. The relation between the elements thus acquires a homogeneity and an anonymity that are able to give rise to unstable structures, which are only perceived in the field of peripheral vision. The plastic object-viewer connection is no longer constant. A virtual movement comes into being. The situation of this perception is thus modified.

• 2. Real movement:

• Animating the plastic object will modify preceding data by incorporating movement and time. Nevertheless, we see this neither as an emotional appeal, nor as an obvious demonstration, but as a new visual proposal.

This new situation, which is outside of the object on a non-emotional plane – between the object and the human eye – constitutes a new basic material for developing new methods of approximation, by using the various possibilities of combination, statistics, probability, and so on.

The very conception of the object can be envisaged either as the immutable unfolding of a given situation, or as a proposal in the various arrangements that give rise to an infinite number of possible visual situations.

Paris, January 1961. GRAV, Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel. Morellet, Le Parc, Sobrino, Yvaral, Stein.

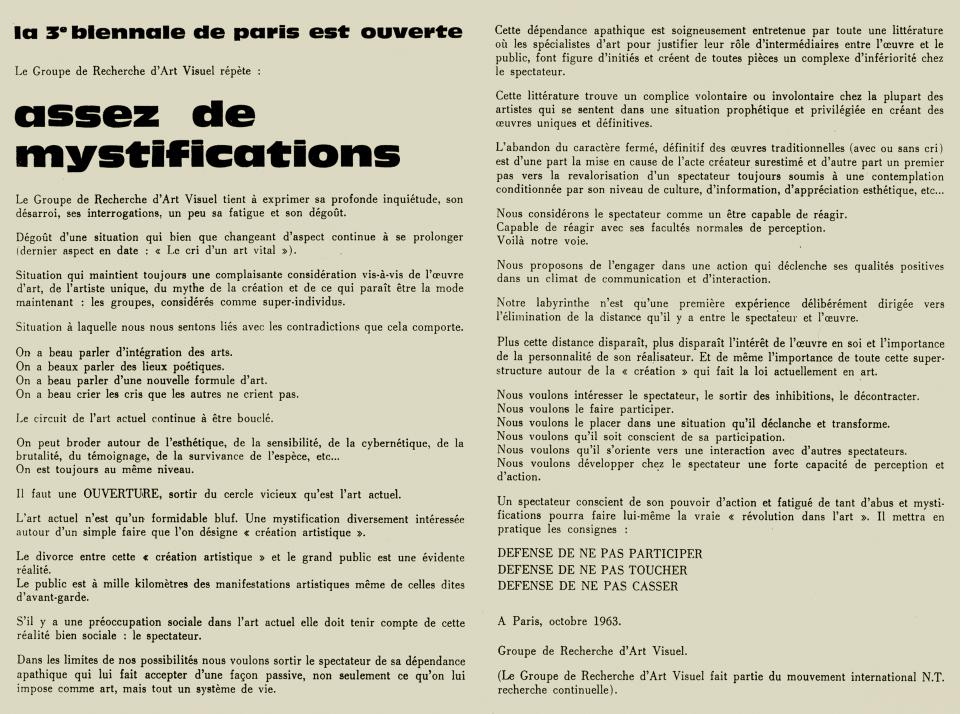

The research presented by the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel in the entrance hall of the third Biennale de Paris was, on the one hand, a transposition to an architectural scale of several of the main aspects of their work and, on the other, an opening up towards new experiences. The point of these experiments was based on the viewers’ participation. The viewer-artwork relationship that the Group developed was further extended and gave the viewer a major role to play.

Here, the traditional focal point was not at stake, which placed the object for contemplation (painting, sculpture, etc.) on one side and the viewer on the other.

The abandonment of the firm, definitive, and static character of traditional artworks was a preliminary step for the Group towards the revaluation of the role of the viewer, who was still subject to a form of contemplation conditioned by their level of culture, information, aesthetic appreciation, and so on.

The Group’s interest in the viewers is different from the kind that might be provided by a scientific mind in search of observations and who would use them as statistical elements by submitting them to tests.

It is also a different path from those who, preoccupied by cybernetics and electronics, leave the viewer at the margins of highly technical productions or consider them as an informative element for producing changes in the artwork by way of electronic cells.

The group’s path is determined by the consideration of viewers as beings capable of reacting. They are capable of reacting with their normal faculties of perception and it is the viewers who gave the proposed experiments their meaning.

Obviously, these are only situations of a fragmentary and limited nature, but their goal is to accentuate the viewer’s role to create new situations where the distance between the artwork and the viewer will no longer exist. In a cursory analysis, here is a list of some situations in which the viewer is engaged to various degrees:

Common perception

A visual marker. Viewers face objects from everyday life. Awareness. Minimum observation.

Contemplation

A visual marker. Viewers face an artwork. Delectation or indifference conditioned by their level of culture, information, etc.

Visual activation (static artworks)

Viewers are opposite or surrounded by a surface with a high degree of homogeneity and vibration. Participation from viewers by means of strict visual solicitation. Saturation.

Visual activation (moving artworks)

Viewers are opposite or surrounded by artworks that undergo transformations. The notion of beginning and end is removed. The viewers’ participation, through their perception, manifests a measure of time in which the artwork is created.

Visual activation (static artworks, displacement of the viewer)

The act of moving or walking around artworks produces more or less accelerated additional changes. Participation due to the viewers’ movements becomes the fundamental element of animation.

Involuntary active participation

By submitting viewers to a predetermined pathway or thoroughfare, they are shown that it is the elements that they displace or move that create the proposed situation (viewers can have a voluntary active partici- pation by returning to their own movements).

Voluntary active participation

Here, viewers face static, semi-static, or moving ensembles. Their participation is necessary to produce the situation or modify it. It triggers a movement, stops it, or produces changes as desired.

Active viewer, element of animation

Here, viewers become an element of animation that will produce an unstable situation for other viewers. Fragmented shadows are superimposed and set in motion, either by walking, or by the viewer’s various movements. So, while participating in various situations, they then create one in turn.

Active viewer, subject of observation

By participating in different situations, the viewer becomes the subject of observation for other viewers.

Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, 1963.

We employ this term, which was previously used at the exhibition Nove Tendencije in Zagreb in 1961. It is a phenomenon that for some years has occurred simul- taneously among young artists in different parts of the world. International manifestations and partial contact is starting to give it a more homogeneous quality. The increasing number of relationships is creating awareness about what is beginning to emerge in the visual arts.

The nature of the New Tendency is not definitive. Indeed, its evolution can contribute new ways of under- standing, appreciating, and positioning art within society, which leads to an implicit examination of its current situation.

Regarding production, a natural reaction occurs on the one hand against the sterile situation that has followed the legitimate rebellions and that produces, day after day, thousands of qualified works, such as: lyrical abstraction, informalism, tachisme, etc., and on the other hand, against the unfruitful perpetuation of the stunted mannerism of geometrical forms which in most cases does nothing more than reiterate Malevich and Mondrian’s proposals. Let us separately consider the current neo-Dada or New Realism movement which is appealing but must be closely analysed. Once the positive aspect of its irreverence in the face of what is traditionally considered beauty is discarded, the contradiction between anti-art and the act of calling an object ‘art’ becomes obvious.

Obviously, the New Tendency, though reacting against these trends, still includes some of their aspects. There is a nuanced production of concrete or constructivist art. There is also a certain trace of tachisme and a few similarities to neo-Dadaism. However, the New Tendency is, above all, the search for clarity. From this standpoint, one must consider the non-definitive work of art, visual appraisal, appreciation in the more exact terms of the ‘act of creating’, the transformation of the activity into a continuous search with no concern other than that of revealing the basic elements so that they may be considered as completely separate from the artistic phenomenon.

On the conceptual level, there is the need to give priority to the work’s visual presence, since in almost all current tendencies there has been the need to resort to extra-visual, anecdotal justifications (this work of art has been painted by the artist dressed in a knight’s suit from the year 1628 in the Middle Ages; or a nude woman rolled over this painting, or even: this button glued onto this relief belonged to the valet of a well- known art dealer with whom the artist is no longer in contact). This so-called extra-visual aspect is found in another form: calling on the viewer’s imagination so that he or she may experience intellectual pleasure knowing that this hermetically sealed box contains an infinite line or the author’s faeces (do not open under any circumstances).

We always find the same so-called extra-visual, this time among the ‘concretes’, for example: for such and such painting, on which six lines are placed in an irregular fashion, the highly rational game consists of knowing that in spite of the apparent difference among these lines, the six are of exactly the same length. Not to mention those who, with geometric or irregular forms, try to create an unremarkable anecdotal link expressed through titles such as: The entire soul summed up . . . or Torn self-portrait, etc.

All of this makes it an easy target for foolish mysti- fications and causes collective blindness. This is why there is a need to clarify and a will to accentuate the fact that the visual presence of the work of art may be the most important characteristic of the New Tendency.

GRAV, Paris, April 1962.