Critical Anthology 1967–2013

Jean Clay -1967

Our epoch will at least have served in that the aesthetic foundations of paintings have been revealed for what they are: an illusion. In an ever-changing, unstable world, in which our sensitive consciousness is in conflict with the incessant movement of forms and the continual transformation of matter, in which we favour the ephemeral over the immutable, the painting, this rectangle of wood or canvas on which pigments are affixed – according to the Van Eyck brothers’ old recipe – now appears to us as a lifeless trap dating from a past nostalgia that claimed to have found in art a way of escaping time, and in the canvas itself, a vehicle for eternity.

What characterizes the art of today is that a gene- ration of researchers has intuitively sensed modern physical realities. This generation has understood how to encompass into its language the ability of the world to continually transform relativity, space-time, the fluidity and flexibility of natural phenomena, and the corpus- cular and wave-like character of energy-matter. With kineticism, art became aware of the instability of reality.

From that point on, the aesthetic phenomenon developed under our very eyes, directly; the artwork was born, twisted and turned, consumed energy, died, and was reborn. A grammarian would say of a kinetic work that it is situated in the present, while a classic work – landscape or abstract – is situated in the past, as it is above all the transposition of an emotional reality previously experienced by the artist. A Kinetic Artwork is simply the unfolding of a physical event in front of our eyes, here and now: the forces of nature – shadows, light, kinetic energy – showing us the huge amount of work they continually do throughout the universe. Kinetic Art is not a realistic art, it’s an art that depicts reality.

This is what occurs with Le Parc: what he offers us with his Continual mobiles, for example, is not the revo- cation of a past emotion emerging out of contact with nature, as in traditional painting, nor is it the creation of a pure object that borrows its laws only from itself, as with concrete art. He offers us nature itself, as we see it. The artwork is the site for a real and current phenomenon, channelled through the attention of the artist, a constituent phenomenon that gives life to it at the very moment we observe it. Le Parc is above all an interpreter, filtering and sieving reality, and the recent developments in his body of work accentuate this orientation. His ‘prepared’ glasses that enable ‘retrovision’, the deformation, cutting-out, or colouring of reality, thus transforming the observer’s visual field into a continually changing spectacle, with a unique atmosphere, form part of this perspective of reality captured and transfigured through the filtering effect of the work. This also occurs with the Mur à lames reflétantes [Wall with Reflecting Blades] exhibited for the first time at the Galerie Denise René in November 1966, which allows the segmentation and multiplication, not of a fictional background prepared in advance, but of life itself taking place in front of the panel. It doesn’t take much for a visitor to pass by it and imagine seeing – this time in reality – the decomposition of movement as Duchamp portrayed it half a century before in his Nude Descending a Staircase.

Le Parc took this concept of the filter-artwork, or the sieve-artwork capturing reality, to its farthest limit in the Mirrors series. The mirror appeared in modern art in 1912, when Juan Gris incorporated a piece into one of his compositions. For the first time, thanks to Gris, a pictorial surface included a piece of changing life, a fragment of reality lying in wait. Later on, some tried to widen this proposition, playing with increasing mastery at the contrast between the figurative and its reflections, between painted matter and life. With his Large Glass (1915–1923), Marcel Duchamp made a decisive contri- bution to this type of assemblage in which fiction and reality are combined and confront one another. Here in our eyes, the elements of the composition are closely mixed up with what is happening behind the glass (the museum decor, visitors passing by), so that we register both what the artwork is showing us (the motifs of the ‘bride’) and what surrounds it (incidents relating to the exhibition). George Cohen’s work Anybody’s Self Portrait (1953) comprises oval mirrors surrounding an oval of the same dimension, within which a replica face is portrayed; Baj, with his broken Mirror (1959), within which different reflecting elements and pieces of tape- stry are combined; more recently, Pistoletto, who in his compositions juxtaposed fake silhouettes with the real silhouettes of passers-by; and so many other artists who see their experiments as an assemblage, a confrontation between true and false, fabricated and real.

What is new with Le Parc1 is the abandonment of this contrasting effect. He does not suggest we combine a given work with the ‘open’ work, static with random, dead with living; he hands us a mirror. Sometimes, it is true, this mirror is covered with even streaks, but the texture is the same and the sole aim of the object is to incorporate into the frame, the mobile ensemble of exterior possibilities that are reflected in it. The rela- tionship is no longer between such and such an aspect of the work, but between the work and what surrounds it. These possibilities are those that constitute matter itself, and the image, and in March 1966 Le Parc listed them as follows: ‘The person who is looking at himself, his way of dressing, the facial expressions he makes, the layout of the mirrors, the distance between them, the movements given to them, the landscapes and the people surrounding it, the lighting, etc.’ To which must be added the fact that viewers also project the mental space of the society in which they live.

Since Panofsky and Francastel, we know to what degree each society engenders a particular visual order – the reverse perspective of the Byzantines, mono- cular perspective of the Renaissance period, cubism’s poly-ocularism – and to what degree this visual order conditions the gaze of individuals in each society. The mirror, always the same yet always different, a neutral field of expansion for all mental architectures, is able to send back, with the same objectivity, all systems of visual organization that viewers unconsciously project. And so, Le Parc’s mirrors are both lasting and fleeting.

In them, not only are physical possibilities reflected but also the successive constructions of the mind.

Although the idea of reflection has such a substantial role in this work (especially in the Continual Mobiles and the Continual Light works), it is in no way an end in itself, but, on the contrary, a way of allowing instability to be perceived – the instability that Le Parc expresses in his other works, like his mountains of virtual volume in which mirrors play no role. If he uses mirrors, it is firstly, as we have seen, because through its very nature, the mirror can only reflect the fleeting. It is also because, thanks to the author’s interventions (even streaks and undulations) the reflective surfaces generally give a distorted view of the objects, which reveals, beyond the immobile appearance, its fundamental precarity. The world is victim to unceasing metamorphosis, but our eyes do not know how to see it; therein resides, through Le Parc’s mirrors, the figurative evidence. Ultimately, these reflection-artworks continually show the world its image, expressing almost as a symbol Le Parc’s stance regarding the problem of art. All his efforts go towards denying the viewer the possibility of drowning in the object, of allowing oneself to be fascinated by the formal composition that is put forward. No more aesthetics: the artwork is there only as prerequisite to reality. It channels it, gives it back its temporary, ephemeral, and changing image (face). It is impossible to succumb to the misleading seductions of the ‘work of art’ when confronted with a work that gives us as a message the very texture of physical reality and that incites us at the same time to make with our own hands the material transformations we deem necessary. Because for Le Parc, it is less a question of expressing oneself than activating the viewer, who must find, when confronted with the presented outlines, meaning in personal intervention and in the choice that modern society has often tended to remove. On one hand, the reduced work has its reflection-function; on the other, viewers are invited to enter, with all their energy, into a dialogue with art; from there, the emphasis shifts, the public’s liberation occurs through the deliberate humiliation of the ‘creator’. For the elaboration of art nouveau – which, since its birth, represents dialogue and co-creation – the pretensions of the artist must firstly be reduced to nothing, and the interminable narrative artists insist on giving throughout all of their plans, about their moral hernias, stuttering romanticism, and a tortured and sublime soul, must be interrupted.

Once again, and quite simply, the mirrors that Le Parc presents to us are like a summary of his deepest thoughts: the blurry faces we see as we pass by give evidence in modern art of the birth of a collaborator who for many years was reduced to passive contemplation only to suddenly appear in full light today. The viewer’s sole function is no longer to respectfully register the messages that arrive from above, but to integrate him or herself as an adult into the creative process.

It would be futile to try to hide this: what is occurring here is the methodical assassination of art and the artist, of form and beauty. After which point, one day perhaps, in a society that has become united in friendship, the time will be ripe for something to be constructed.

1. We must, however, note that in 1945, lacking a future and with a com- pletely surreal, remarkable intuition, Man Ray created a ‘self-portrait’ with a supple mirror that responded to the touch of a finger. To do this, he used a chrome plate for varnishing his photos. The ensemble was surrounded by a whimsical frame designed to simulate and parody the frame of a painting. We could also mention, as an aside, the rigid mirror imagined by Soupault during the Dada period, entitled Portrait d’un imbécile.

Jorge Romero Brest – 1967

I met Le Parc some time after the Libertadora Revolution broke out. At the time, we were partici- pating in a committee in charge of modifying the study programmes of the school of fine arts. He was stubborn, armed with a rare spirit of independence. I immediately liked him. The connection between us came more from the ideas and emotions that resulted from them than from the artworks themselves, which he had made as a student graduate at this school. The period was more about political struggles than artistic ones. In 1958, he presented his candidacy for one of the scholarships that the French Embassy provided. I was on the jury and so I warmly supported him, even though I don’t recall now the artworks that he had presented. What mattered was the man, his curiosity, his fervent desire to succeed. After his first year in Paris, I didn’t manage to get his scholarship renewed, but Julio Payro, another member of the jury, obtained one of the grants from the Fonds national des arts for him; so that was how he was able to stay in the city.

Ever since, we remained united by an affection based on mutual understanding. That is why, when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship asked me to participate in writing the special catalogue of its works for the Venice Biennale in 1966, I wrote: ‘I am writing this essay, not to present him but to share in his adventure . . .’ an adventure that ended, as we know, by the attribution of the most important prize to Le Parc.

This prize was also an award for those who had believed in him – especially Julio Payro, Hugo Parpagnoli, and Samuel Paz who had decided to send his artworks to Venice, and for Argentina, which already had major awards under its belt obtained by Alicia Perez Penalba, Antonio Berni, and José Antonio Fernandez Muro at previous biennials.

When I saw him again, in the Parisian winter of 1959–60, he was even more determined than during his post-revolutionary period. But he was now dealing less with politics than with art, determined to find the point of sublimation – if I may say so – of his experiments around Vasarely, so that his drawn or painted images would be ‘necessary’ and animated, which those of his master were not.

To return to this text, I had attempted to make a timeline of his evolution, ‘from the early works in Paris, when he was looking for the dynamic of things in an indirect manner through geometric shapes, through to his encounter with the dynamic of light that enabled direct access to the dynamic of things.’ If I am repeating these words it is because I would be incapable of summarizing this evolution any differently. All I might add would be that he was undertaking a silent struggle against the concrete and flat image, as arrogant in its traditional static nature as it is full of symbolic enchantments.

A dramatic struggle – as well as a silent one – that explains his personal production, the success of his artworks, and even his modesty. Which worries me, in fact; it is as though he were resorting to it to tend to his wounds, fearful of the idea that others might open up, while he possesses all the characteristics of genius.

Yet I still wonder sometimes if by relinquishing his in- dividualism – or more precisely the vanity of being an individual – he is not revealing precisely the existence of this genius.

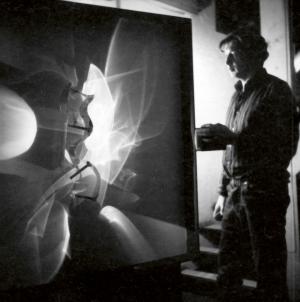

During these few days that I spent in Paris with him, Le Parc was unfolding progressive sequences onto sheets of paper that he was skilfully manipulating in front of me, thus initiating me – alchemist of flat formats – into the secret of his ostinato rigore. His unwavering attitude greatly impressed me, but what intrigued me most was wondering how he was going to get out of the prison of his own making. But then the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) was created, when they all left their painting-prisons to resolve the problems of the three real dimensions in space. The progressive sequences were placed in service to real displacements and rotations, thus giving rise to the idea of the Continual Mobiles and the Continual Light works.

Le Parc then tried to resolve the traditional opposi- tion between content and form. The movement of the small pieces, enhanced by the direct light and further still by the reflected light, when the other disappears, means that the spectator penetrates a work or there is no fragmentation, or everything is content and every- thing is form. To achieve this, he varies the sources of light and multiplies the possibilities of form by using several different materials.

Its originality was already undeniable, which is why his artworks were presented at the Venice Biennale in 1964. Of course, his work was the main attraction of the Argentinian room but also that of the entire biennial. It was impossible not to feel the power of the impact of the little labyrinth that he had built with luminous objects. I’ve heard tell that some members of the jury wanted to give him a prize, but pop art was in fashion and the grand prize for painting was attributed to Rauschenberg. Le Parc did not have to wait long for his turn, as those who encouraged him for the following biennial had understood.

We had met in Paris beforehand, during the exhi- bition of the New Tendency (Musée d’arts décoratifs, 1964), then we saw each other again in Buenos Aires where he had come to organize the GRAV’s exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts and participate in the Torcuato Di Tella Institute’s international award.

He obtained a special ‘acquisition’ award there, thanks to the votes of the jurors: Clement Greenberg, Pierre Restany, and myself.

Le Parc had matured, as an artist and as a man. The other groups that had been constituted in Europe did not tarnish in the slightest the prestige of the GRAV, or his own, obviously. More than just an excellent artist, he was a serene guide, open to the world, whose artworks are not even individualized, creating a visual symphony, combining imagination and thought.

I had the chance to test it during the various gather- ings at the end of that 1964 year, one of which was at my place, with some very young painters such as Marta Minujin or Dalila Puzzovio, another from the Di Tella Institute, with architects. Quite self-possessed, Le Parc expressed clear ideas and dispensed advice, without pedantry, responding to the objections given to him with surprising assurance and great confidence in the future.

We met again in 1965, this time in New York. The GRAV was exhibiting at The Contemporaries Gallery and Le Parc participated in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art entitled The Responsive Eye. One of his pieces – small and solitary, simple and original – had fascinated me. In it, I understood the endless poetic possibilities that could be obtained using his method, despite the mechanisms in action.

Which brings us to 1966. It was a remote encounter, by way of the prologue I’ve already mentioned and in which I emphasise the value of his œuvre ‘because he uses the simplest means to produce lighting effects or compose interplays between various objects and because the mechanical precision does not preclude either the variety of possibilities, or the surprise. To which is added the poetic parable of his creative imagination, attentive to the considerations of modern life but acting within the folly of marvels.’

Note that such a parable, no doubt representing the trajectory of any artist, takes on a whole new level with Le Parc. This is why ‘it would be a mistake to focus on the light and reflections, on the mechanics and geometry, even though he uses light, draws on mechanics and knows geometry,’ I wrote in this same text. Because in Le Parc’s hands these elements and this knowledge penetrate their original meaning to integrate within the whole. This is fundamental, which is why I am emphasising it. Replacing concrete and flat images that refer to the space with the abstract and extraordinary images that movement generates fluidly identifies the dialectic that eventually leads to placing humanity within functional truth. A way of shortening the distance between life and art, by trying to eliminate ideas and diktats, and even feelings and desires, the traditional obstacles to any free act.

It is unsurprising, then, that Le Parc and his friends have monopolized the viewers’ interest. It is not just for social reasons, as is generally thought. Destroying the work of art as a unique object of individual expression amounts to giving rise to time as a factor of perma- nent creation. The modern way of life, modernism, has inherited fans of concrete and static geometric forms. All of this without the aggression introduced by the neo-realists or neo-Dadaists, without the confusion that the ‘Op’ artworks elicit, one step away from erasing the habit of decorating rooms with works of art and nonetheless partially resolving the commerciality of art with ‘multiples’ that they create themselves or allow others to make.

However, to situate Le Parc within today’s panorama, he continues to evolve within the manual and well-crafted field of art. Despite the fact that he depersonalizes his creation and develops the relationships between the artwork and the viewer, accepting the industrialization of ‘multiples’ as a lesser evil, he remains a creator of objects that allow life or metaphors to be reflected.

It is true that he relies on the aesthetic predisposition of human nature, pushing back its limits, but not as the organizers of ‘happenings’ or predetermined situations do, through massive means of communication. Unless in the end his system proves to be the most authentic in this confused search for a ‘profile’ that drives the young people of today.

I’m ready for our next encounter – with more curiosity than ever.

Published in the exhibition catalogue of the Le Parc retrospective held at the Buenos Aires Di Tella Institute, 1967.

Julián Gállego – 1977

About ten years ago, Damian C. Bayon, my Argentinian colleague in Pierre Francastel’s small Parisian group, invited me to dine with him at the home of Julio Le Parc, his fellow-countryman. The workshop was big, dinner delicious, conversation rare. I think that by nature he preferred writing and especially inventing. Also, at this time he had adopted a far-left political position, which must have influenced his personality. It is possible that Le Parc, the child prodigy of a bourgeois consumer society that had imprisoned him in a gilded cage, was aware of the absurdity of his situation – a cult of per- sonality in opposition to his own ideas. This is perhaps why he spoke so little and why this dinner, which I had so looked forward to, seemed to pass so slowly.

I had already known and admired Julio Le Parc’s work for many years. To check this, I looked in my collection of columns that I had sent from Paris to the magazine Goya, and I found no fewer than fourteen, some quite long, all full of praise for this artist that I had disco- vered for the first time at the Galerie Creuze in 1962. This was when what could be called the golden age of South-American abstraction began. In the 1960s, one of the richest veins of Parisian artistic production was born in South America, more particularly, in Argentina and Venezuela. At the Galerie Denise René (who was a pioneer in the optico-constructivist movement), Le Parc was continually present, the star . . . Being successful in Paris meant you were successful at a global level. At the 32nd Venice Biennale, some of his works drew attention. This was in 1964, the year in which Le Parc’s group had held an exhibition under the label of ‘New Tendency’ at the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris. The Republic of Argentina had thus felt that the time was ripe to organize what in the decadent Paris of old was known as a ‘one man show’ honouring Julio Le Parc, at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966, the curator of which was my great friend Leopoldo Torres Aguero. I arrived in Venice in September as the Biennale was just about

to close its doors. The ‘show’ was starting to become a little worn after the visit of thousands of summer viewers, who had not been able to resist taking a sou- venir – nearly all of the glasses were gone, as well as most of the mirrors with which the artist had captured the fragmented, successive, and distorted aspects of optical reality in the pavilion, where the viewers, by touching them so much, had also damaged the small electric motors in his installations. But the most sur- prising thing in the whole story was that the jury at the Biennale had awarded the Grand Prize for Painting to a work in which painting, strictly speaking, did not figure. The organizers themselves had seemed to be leaning towards sculpture, if only for its three-dimensionality. It was as if there was a contradiction between a technolo- gical art that didn’t function and a prize, well deserved it must be said, but that was meant to reward the best painter. One of Le Parc’s many contradictions.

He had arrived in Paris at age thirty in 1958, thanks to a grant from the French government, who was full of admiration for this posthumous son of Bauhaus and Vasarely. He lost no time. One year later he was trying, with the help of Spanish artist Sobrino, to free himself of this somewhat stifling influence. Another year on and he had become one of the founders of the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, a team who took action so brilliantly (and in such a refreshing way) in the new Paris biennials. At least until the team's dissolution in 1968 – that year of dissolutions, including, some had believed, of art markets and individual artists.

This is what Le Parc must also have thought as he refrained from speaking while seated opposite two members of the hedonistic world of the art critic – namely Bayon and I. Some time later, he turned down, for political reasons, an exhibition that had been offered to him at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. No doubt he saw it as too official, too embroiled with capitalist society.

But in which society did Denise René move, whose New York branch of the gallery had as much success as the one in Paris? What is an artwork for the people if the people do not understand it and cannot even see it?

In winter 1970–71, with a healthy dose of opportunism, Denise René exhibited works from 1959. It is a shame she hadn’t exhibited them at the time. Le Parc’s variations on a spectrum of fourteen colours steered clear of any artistic intention, opposing Vasarely’s affirmations in regard to the right of the artist to intervene, effect changes, and thus express his personality. It was almost a betrayal of the combined humanity and pure vision of Le Parc, who no longer owed anything to his master. It is true that the exhibited works did greatly resemble those of Vasarely.

Last spring, Denise René presented a new Le Parc exhibition entitled Modulations. It was disconcerting in the way it cultivated the trompe l’œil, in total contra- diction to his previous corpus that was ‘realistic’ in the American sense of the term, that is, exempt from decep- tive elements such as shadows or gradations suggesting curved, spherical surfaces in the form of trees, piping, or interlaced lines. However, the artist describes this work as being ‘the continuation of a position loosely adopted at the beginning of my research in 1958.’ A position that was twofold: the first part, related to the means of situating oneself and reacting to real life, analyses the artist’s position, his contradictions and limitations, the way in which he is manipulated or used by the cultural milieu, his dependence on those who have the decision-making power, etc., and tries to combat this situation, from inside and outside of his work; the second aspect is his continually experimental behaviour that is happy to take the risk of making mistakes . . .

Le Parc believes that repeating a formula that has already been experimented with is not a good idea: ‘In my study and research, and over the course of experimentation, it is important, from time to time, to question my accepted conclusions, while continuing to analyse and reflect on my discoveries.’ This very personal approach seems quite ‘artistic’ to me. A scientist, let alone a computer, would never reject repetition and would never set off into the unknown as a ‘traditional’ artist would.

The Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel established the idea of an open, non-definitive work, subject to the possibilities that the viewer-actors (even if they steal the mirrors and glasses) impose on it. ‘It is the over- valued role of the artist-creator that is in question.’ ‘Let’s imagine that instead of the lone and inspired artist, researchers appear, inventors of elements and situations, animators who through their creations succeed in highlighting the contradictions of art today and, by trying to establish more direct connections with the viewer, succeed in creating conditions for opening a pathway that will allow the Art/General Public antinomy to be overcome.’ As best I can, I have translated a small manifesto from French [to Spanish], dating from May 1966, which was included in the catalogue published by Denise René to celebrate the presence of Le Parc at the 33rd Venice Biennale. A camouflaged cult of personality, as out of the entire group, the artist who received the kudos and publicity here was Julio Le Parc.

This contradiction is obvious and has been evident in all the collective exhibitions that I have visited. Le Parc is not a skilful labourer or a laboratory employee or a sophisticated computer or a biological or political cell. In the semi-technological art of our times, there are many works that are not even artistic and that only differ from a utilitarian machine in that they produce nothing concrete: their nobility, like those of hidalgos, resides in their uselessness. Schoffer himself was not able to free himself of the doubt that these works, as well as turning and projecting coloured rays, could also decorate biscuits or plastic glasses, and that their ‘artistic’ quality only exists because they don’t. A work by Le Parc created in complete freedom, without an anti-Vasarely premise, is different to a work by Vasarely or anyone else.

Don Felipe de Guevara recounted in the middle of the sixteenth century that when Moorish architects had finished designing their buildings ‘with art and reason’, they added: ‘may Allah grant you mercy! . . .’ Well, in many works that are ‘made with an enormous amount of art and reason’, a certain ‘indefinable je ne sais quoi’ is missing. Heaven has granted this je ne sais quoi to Le Parc.

Pierre Restany – 1995

There are some destinies that are like the threads of a tapestry: in the upper or lower part of the loom, some points are more sensitive than others to interlacing or braiding. The example of Julio Le Parc for me is of the utmost significance. Our destinies have crossed paths on several occasions and have thus stitched out the outline of a warm friendship despite its irregularity.

Julio Le Parc was the kingpin of the GRAV before becoming its iconic representative. The Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, who were friends with Denise René’s grandson, was founded in Paris in 1960, at the same time as the group of new realists. I followed the action of these young Kinetic artists with great interest. They shared with us, the new realists, the awareness of having to act within an industrial society at its dying peak. Julio Le Parc and his friends in the GRAV were highly sensitive to their means of insertion into the urban milieu, and I recall, in 1966, a fantastic expedition through Paris, criss-crossed with different stages in a performance. Geometry had taken to the streets, and I followed, with curiosity as much as passion, this entry of art into the streets. After their famous labyrinth at the Biennale de Paris, the members of GRAV had to slacken the pace of their collective efforts. Their period of common action was brief, as indeed was that of the new realists. They were both entirely recycled by this consumer society that was central to modernity.

Beyond this sociological platform founded upon the art-industry relationship, our paths crossed again and on several occasions. I met Julio Le Parc in Buenos Aires, in particular in 1964.

I followed his anti-establishment action in May 1968, his arrest at the Renault factory in Flins, and I supported all the efforts made by Denise René to help him. Julio Le Parc was not permanently deported from France, and that was truly a good thing. He is one of the artists that has contributed the most to the opening of kinetic painting towards horizons of freer communication and language. Meanwhile, in 1966, he was awarded the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale. Two years afterwards, it was the Rauschenberg Prize that conse- crated both the emergence of the new American school and the globalization of pop style art – the hand had been dealt in Venice. The venerable art institution now had to crown the geometric, Kinetic artistic movement. ‘Op after Pop’ as we said at the time. I remember that month of June in Venice. It was unbearably hot during the opening of the Biennale, and everything took place at the Florian rather than the Giardini. Everyone thought that the jury was going to crown Soto as the great guru of the penetrables. A last-minute reversal on the part of Palma Bucarelli meant that things turned out differently. While remaining in the spirit of kineticism, her choice settled on the most visible personality in this second generation of the artists in the movement.

Julio Le Parc thus became the GRAV’s representative figure, a fact that threw disarray into the souls of his co-members. The Grand Prize at Venice sounded the death knell of the group’s existence.

I subsequently saw Julio Le Parc in various places around the world, and in particular in Cuba where he had made himself one of the most active architects in the official recovery of the Havana Biennial, by running a creative workshop.

For me this character is a creative bird, who, from time to time, crosses the sky in my memories. Having said that, I have greatly appreciated his chromatic development and his rainbow period, which I identified with the intellectual nomadism of this beautiful spirit, who in his work has known how to admirably reconcile heart and reason.

Mario Benedetti – 1995.

As a layperson in both the techniques and propo- sitions of plastic art, I must take refuge in the limited territory of the viewer of art, an ambiguous condition without value in which any judgement relies on a predominant feeling of enjoyment or disdain instead of on rigorous professional analysis. This analysis is what I try to do when I practise my profession of lite- rary critic, given that in this domain, a different level of responsibility and rigour is expected of me. So it is only from the viewpoint of the viewer, or even voyeur, that I can understand Julio Le Parc, as his body of work has always brought me joy and vitality, and stimulated my imagination.

It would be absurd to claim that his Kinetic Art, as if in response to traditional immobile artworks from across the ages (and which include so many memorable endeavours), is in any way a compromise with the centre or contours of reality.

However, by giving back a sense of value to the viewer’s participation and by continuing (in his words) ‘to search for possibilities that create situations in which people’s behaviour can lead to action’, Le Parc goes beyond technological development and places himself in the centre of his fellow humans’ existence. And this inventor, this maker of communication introduces a new dimension of social significance into the artistic task.

In the kinetic capacity of this artist, which is both mobile and mobilizing, there is a playful vocation that arouses not only the curiosity and interest of children (the ultimate blank-slate pleasure-seeking audience) but also that of those adults who still live with memories of their own childhood.

It is obvious that Le Parc has enhanced his prestige in the difficult European space, more specifically in France. For all that, does he represent the condition of the Argentinian artist? I suspect that his ‘Argentinianism’ is demonstrated in his way of assimilating what is European. I am reminded of the anthropophagy of Oswald de Andrade, a literary experience specific to Brazil that Antonio Candido described as ‘the devouring of European values, which had to be destroyed in order to incorporate them into our reality, in the same way that cannibalistic aborigines devoured their enemies in order to incorporate their virtue into their own flesh.’ Just like this experience, that left its mark on its time, for Le Parc the new is incorporated, not superficially, but with the breadth and methodical examination that comes with maturity. His research and his way of taking on what is new are so convincing that no one doubts that the incorporation of this newness should result in another, original dimension. The new-other.

It has been a while since I have attended one of Le Parc’s exhibitions; I saw some of his exhibitions at the Rio de la Plata and in Havana. I remember that two or three years ago, I was able to observe, in an exhibition at a Madrid gallery, how even in returning to the blackboard, he gave another turn of the nut to his incredible imagination by giving mobility to his apparently immobile images.

I have the impression that here, Le Parc was exercising anthropophagy, no more or no less so than Vasarely, but with a transformation and enriching of the French- Hungarian artist’s cold kineticism through the mobile warmth of the Argentinian.

This is why I believe that even with his extended stay in Europe, Le Parc (as Soto, Matta, Cruz-Diez, Gamarra, Sobrino, and so many other Latin Americans have done, with different and sometimes only distantly related nuances, optical effects, and styles) gives form to an art that bears his stamp and individual mark, an art that allows Latin American fantasy, wakefulness, and ingenuity to be observed, entering and ransacking an enormous and consolidated European heritage to produce a thought-provoking and dynamic rebirth that encompasses both sides.

Jean-Louis Pradel - 2013

In October 2012, during the Nuit Blanche in Paris, a space-time that was perfectly tailored to him, Julio Le Parc invited a crowd of nocturnal wanderers to an extraordinary double event. On the Place de la Concorde, he bathed the Obelisk in a dancing light whose volup- tuous convolutions transformed the glorious monolith in the style of Loïe Fuller’s diaphanous veils. Through the magic of cleverly controlled lights from four powerful projectors placed at its base, whose brightness was filtered through moving discs, the implacable white light was sliced up and cut into supple fields where the lightning-swift radiance curled into gentle scrolls to finally give way to a desire for infinite and random fleeting impressions, to the very depth of the cold night, dressing the thousand-year-old granite erection in a mellow and soft incandescence, like an exchange of confi- dences. At the other end of the Seine, in the construction site of the future shopping centre at Beaugrenelle, a dozen small totems projected their vibrating light from every direction into the pathways of a labyrinth made up of hundreds of strips of semi-transparent tulle, where the crowd of visitors experienced a joyful visual instability in which bodies seemed animated with the spirit of a comical St. Vitus’s dance. It looked as if everyone was jumping. People delighted in losing and finding each other, calling out to one another, laughing and taking photographs of themselves, consenting victims of an enchanted world finally rid of the inconveniences of weight and the need for gravitas demanded by works of Art.

Through this double event, Julio Le Parc revealed himself as a great organizer of public space, not in order to submit it to his fickle whims as a creator, show his colours and forms, or impose an ideal aesthetic regime on the city, but to go out to meet as many people as possible and invite them to a feast of perception where anyone can become a master craftsman, while the artist himself sits back from his visual proposition of a system that willingly welcomes the twists and turns of fate. Into this gap comes an air of freedom, giving the viewer a chance to breathe it in, far from ‘stifling culture’ and its conventions. Public spaces suit Julio Le Parc so well because within them he can make the infinite enter more easily. At the heart of the huge Place de la Concorde, open on three of its sides, just like the ‘in progress’ construction site at Beaugrenelle, Julio Le Parc’s intervention can play at pushing back the limits at will, so as to better invite the more perceptive art enthusiast as well as those strolling by distractedly to discover new horizons, perspectives, and spaces, outside of any classified mental or aesthetic category, allowing a stream of emotions to take hold of bodies and hearts.

Ever since the GRAV’s famous collective experiments, and in particular the Day in the Street on Tuesday 19 April 1966, Julio Le Parc, crowned with the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale in the same year, has continuously aimed to be a catalyst for unexpected situations, and to do that he has done away with the contemplative attitude and silent passivity expected before the sacrosanct revelation of art. This is how Julio Le Parc, through all means possible, orchestrates a joyful confusion of genres that does away with the laws of distinction. Instead, a Copernican revolution maintains this merry chaos far from the epicentres around which the upholders of the art world gravitate, satisfied with cultivating their own prerogatives and sheltered from the ordinary world with its ignorance and disruptive effects. For Julio Le Parc, artistic practice can only take place at the heart of the city, to the point where the name ‘artist’, totally hackneyed in his opinion, disgusts him. He instead prefers that of a ‘simple labourer in visual research’, as indicated by his ever-present blue shirt, whose front pocket displays, just like a row of medals won on the battlefield of plastic arts, a beautiful palette of pencils and felts of all colours. He thus joins the famous portrait of John Heartfield, painted by his friend George Grosz in 1920, and demonstrates his ‘taste for blue overalls’ like the protagonists of Dada Berlin, which Raoul Hausmann explained as their desire to be understood ‘as engineers: we want to build, assemble, construct.’

An indefatigable and non-stop experimenter, in 1970 Julio Le Parc treated himself to a proper base when he took over a former industrial laundry in Cachan, a suburb in the south of Paris. The workshop was immense, with many tools and ample space. For this researcher of absolutely everything, this was not a luxury but a necessity, as he needed to be at the heart of a lively hub where everyone was welcome. Artists from South America would call in, colleagues of all sorts, this or that friend in need of a studio space, young people involved in collective work, and a host of friends who would come together for an ephemeral exhibition, a gigantic barbecue set up in the courtyard, or a party, where of course Carlos Gardel or Astor Piazzola were not forgotten. Julio Le Parc is not one to shut himself up in an ivory tower. He needs people and noise. A tireless worker, he also needs a a community building, a sort of giant bazaar buzzing with activity, rather than a factory like his exact New York contemporary. He is an ogre. You should see him devour prime beef ribs – Argentinian, of course – sometimes smuggled in mysterious blood-stained mail packages slipped into the diplomatic pouch! He is a food lover who cannot resist sweet delights and succulent desserts. A natural-born charmer, he enjoys giving an irresistible smile or a cheeky wink and employing his ever-present wit. But although he is outstandingly warm and welcoming, he is definitely not a pushover. His cap firmly on his head of silver hair, he is like a captain on a long-distance journey holding his course.

For half a century now, a resolute desire for clarity has driven Julio Le Parc to disrupt the night, identify within it the promise of an inexpressible morning, and shed light on the dark artistic business that restricts the fine arts to shadowy twists and turns. Against the arbitrari- ness of ‘value attribution’, timid small-mindedness, and arrogant boorishness of experts, a democratic dawn must rise, open to all. Julio Le Parc and the GRAV were right at the very heart of the ferment that took hold of Paris during the 1960s. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, rekindled in 1962 by the delivery of Soviet missiles to Cuba, the intensification of the Vietnam War, social and political violence, and ongoing archaic dictatorships in Spain and Portugal, anticonformism was de rigueur in all domains, from the Nouvelle Vague to the social sciences, from Yves Saint Laurent to Paco Rabanne and his first dress made of aluminium squares borrowed from Julio Le Parc, from situationists to left-wingers. A new generation everywhere wanted to bring past dogmas and values to an end. It was a question of creating a new world, everywhere. And imagine this movement deepening until the storm broke in 1968. This is when the uniqueness of Julio Le Parc (who had already emerged as GRAV’s leader) and of his activism and tracts, freshly graced with the aura attributed by the Venice Biennale, realized its full potential. It was to be a resounding NO!

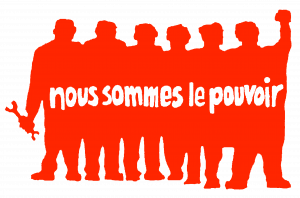

Le Parc was omnipresent at the Atelier populaire des beaux-arts, where the famous anonymous serigraph posters came from, and on which, among other things, the famous chain of ‘We are the power’ workers could be recognized. The artist, who had returned from Mexico, was arrested on 6 June 1968 on the Saint-Cloud bridge, victim of a police raid set up on the Western motorway exit that led to the Renault factories in Flins, where a demonstrator had just been killed by police during riots. Against the advice of several ministers, Raymond Marcellin, the Minister of the Interior, a public servant within the former Vichy government and a believer in an international socialist conspiracy, decided to deport him. Petitions and press campaigns led to his return five months later. In the meantime, the GRAV had dis- banded and Julio Le Parc withdrew his artworks from the Documenta in Kassel, a decision that he explained in a manifesto text published in the Opus International magazine. In November that year he resigned from the governing board of the Salon de Mai. Finally, in a display of impertinence, on 1 April 1972, Julio Le Parc played heads or tails to decide on whether his planned retro- spective would open at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris on 20 June. In front of a general assembly of artists that he had called together at the museum, he gave his son a coin. The die were cast before the coin had even fallen – heads means no! At the same time, as part of the FAP (Front des Artistes Plasticiens), he refused to participate in the 72/72 exhibition, known as the ‘Pompidou exhibition’ due to the extent to which the President of the Republic had committed to it,

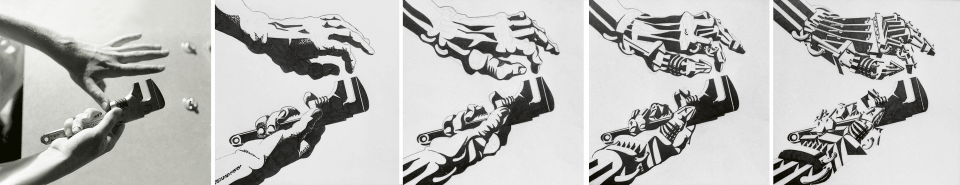

prefiguring his major project developing the Beaubourg plateau. As contemporary art increasingly became a state affair, Julio Le Parc preferred to participate in all sorts of anti-establishment collectives. With the Brigade of Antifascist Painters, vast murals and banners were produced, including ‘For Vietnam’, ‘For Chile’, ‘For Latin America’, ‘For Nicaragua’, and ‘For El Salvador’. With the Torture collective, he exhibited seven large-formats at the 23rd Salon de la Jeune Peinture in 1972, which with unbearable realism denounced the acts of violence committed on political prisoners by South-American dictatorships. The following year, at the same Salon, with his students from the UER in Saint-Charles, which Bernard Teyssèdre had just created and where he had been teaching for two years, he presented Les Mains [Hands], a series of large-format, black-and-white works where flesh became metal.

In this way, then, a history of the tireless militant artist Julio Le Parc could be written. Intransigent partisan for a guerrilla culture, this contemporary of Che can be found on all fronts where art is practised. Utter commit- ment combined with flawless lucidity has resulted in the artist’s grandeur. Presiding over the disaster of the thirty previous years, with its triumph of ultra-liberalism and the decline of intellectual acuity in excessive media exposure, Julio Le Parc’s vigilance is all the more salutary. Paris, his adopted but long ungrateful city, has finally attributed to Julio Le Parc, already famous in so many towns and capital cities, the position he rightfully de- serves as a giant in the modern-art world. This is the promised dawn rising above the dull greyness of the art scene encumbered with lofty private jokes, indulgent provocations, and ‘deceptive’ reuses. The fresh breeze from the wide open seas has risen once again. The reunion is all the more refreshing in that it dazzled new generations at the Centre Pompidou-Metz in autumn 2011, at the heart of the ‘labyrinthine variations’ of which Julio Le Parc could only be the pivotal point, at the Palais de Tokyo, the venerable space for the best of emerging art, and at the heart of the vast historic saga that in spring 2013 invaded the Grand Palais to cry out loud and clear ‘Luminous! Dynamic!’ Beneath the apparent ease that signals the work of a master, the instability cultivated with passion by the work of this experimenter, Le Parc is making colour popular again. Bright lights and primary colours are on the menu, ‘for your eyes only.’

A rebel is at the party, and what’s more, he is inviting us to share it with him. Therein resides his nonchalant, slightly insolent elegance, which he displays with the assurance of one who has never deviated from his course. In his home port, on the doorstep of the flagship safely moored in the small Rue de Cachan, the intercom lists a good dozen Le Parcs. His wife Martha has a studio of sumptuous textile creations, honoured with exhibitions around the globe. Their three sons, artists in their own right, willingly attribute a share of their ability to Julio. Jean-Claude, the eldest, an expert in neurological art, has also created his father’s website and virtual museum. Gabriel, a talented videographer formerly involved in decorative arts, has directed superb films on the exploits of Julio Le Parc, such as his glorious return to Buenos Aires upon the restoration of democracy, which culmi- nated in a gigantic firework show to the music of Astor Piazzola. Over the past six years, Yamil, the youngest, a skilled tango singer that you have to hear sing Volver a cappella, has also been the kingpin of his father’s revival, both in France and Argentina, where his home town of Mendoza has opened a gigantic Julio Le Parc Cultural Centre. Elie, Elizabeth Le Parc, who is also the head of an artists’ collective, works among his archives and papers, and let’s not forget among his assistants, Santiago Torres, who is himself a knowledgeable multimedia and computer artist. To this exceptional polyphonic tribe can be added the five boisterous grandchildren: Luna, Mateo, Salvador, Alma, and Iman, who still jump onto the knees of the great patriarch! And that’s not counting passing friends who stay for varying amounts of time in this surprising city-workshop that has been conside- rably extended and done up in line with projects and models devised by the master of the house in his role as architect emeritus and which was inaugurated in 2008 for his eightieth birthday. For his eighty-fifth birthday, on September 2013, the opening of a huge exhibition is planned in the newly completed contemporary art space in Rio de Janeiro.

Nothing is left to chance in the world of Julio Le Parc, despite him willingly and idiosyncratically summoning it in his visual propositions, through infinite combina- tions. As a perfectionist, he is continually drawing and fine-tuning things with sketches and detailed plans. Like all great masters, he attributes importance to the most modest element as well as to the largest. An example of this is the careful preparation, down to the finest detail, of his workshops held in Madrid in 1985 and Havana in 1986 during the second Biennial, of which he was practically the master craftsman. But also the exhibition of his ‘light years’ in the Brenne Park in 1995 or at the Electra Foundation the following year, not to mention the Tour Saint-Nicolas in La Rochelle and the Île d’Aix in 1999, or the surprising meeting organized by the Maison des Arts de Bagneux in 2011 between Julio Le Parc and Yann Kersalé, who can be included, like so many today, throughout the world, among his most ardent admirers. Each time he demonstrates the same rigour, the same demanding standards, the same fastidious care of the scrupulous professional who checks everything, controls everything, and carefully outlines his instructions to managers and artisans who soon become his most devoted followers. And so the party begins, both serious and light-hearted. Is the tango not a sad song that we dance to? The art of Julio Le Parc is surprisingly musical. Silence, which is only disturbed by the rattling of motors, bullets in a killing game, or punches thrown against effigies of established bodies, finds itself inhabited by innumerable melodies. With the ability to elegantly disconnect from passing time and the time he creates, the party brings together the most diverse dreams only to disperse them to the farthest reaches of unexpected horizons, accompa- nied with fragile and decisive moments, as if it were a question – more than ever, as a matter of urgency – of replacing beauty with happiness.