After the GRAV

For quite some time, the group had been practically nonexistent. The efforts made at the beginning of the year proved to be insufficient.

There was a clear indecision around carrying out new initiatives. What little had been done in the name of the group, with neither the agreement nor the collaboration of all of its members, did not qualify as collective work. Because of this internal deficiency, the possibilities of collective work were scarce; the group therefore found itself (and its members in particular) assimilated into the art world. It was a complicit laissez-faire situation that was compensated neither by new experiences nor by the intentions described in the ‘position statement’.

A lack of will and ability with regards to collective work (naturally justified by some of us) made the group go along with the circumstances. Each new initiative carried along a dead weight, due to lack of determination, paralysing slowness, forced collaboration, fear of ridicule, forced acceptance refuted by the facts.

And the closed nature of the group made us ‘members for life’ and impeded renewal and naturally limited its range of action; thereby allowing the prestige of the group to be used with the minimum amount of effort.

Thereby, the new, and consequently risky initiatives such as ‘A Day in the Street’, required years of insistent requests so that it could finally be carried out. And even at the last minute there were still many uncertainties.

In May 1968, the group was practically nonexistent. It could not be counted on, it was not needed. Each one of us was taking a position and behaving in response to the events as we each saw fit. This situation highlighted the divergence between the group’s capacity for action and the demands of reality.

My experience within the group, during the eight years it existed, has been very positive. In spite of being in favour of its dissolution, I believe now more than even that collective work is the only valid way to try to disrupt the established values that we find throughout the art world. This commitment to collective work proves to be impossible within the group, due to its evolution, composition, and the demands of this extreme situation.

To clarify my position, see the text published in French in Opus International (issue 6).

Julio Le Parc, December 1968

Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Montevideo, São Paulo, Valencia, Caracas

After a four-month stay in a few South American cities (Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Montevideo, São Paulo, Valencia, Caracas), and having attended the Symposium of Intellectuals and Artists of the Americas that was held in November 1967 in Puerto Azul (Venezuela); having had, in addition, on countless occasions, the possibility of conversing with many very diverse people, I felt, upon my return to Paris, the need to clarify and reaffirm certain aspects of my position.

In Paris, I shared my concerns with several people, including my friends from the GRAV and Robho. The latter asked me for an editorial for their forthcoming issue. So those were the circumstances behind this text which had been limping along since November (four months). I say this in a critical and self-critical manner. Because I think that it’s important to act. Act on every occasion. Act to create new situations in which a more concerted, more orchestrated action could be developed. Act even at the risk of getting it wrong.

During my trip, I’d done four exhibitions representa- tive of my research, with very broad public participation (Buenos Aires: 180,000 visitors in sixteen days).

I didn’t want the happy, spontaneous fairground atmosphere that could be seen among the visitors to my exhibitions (most of them initiates) to be assimilated to the attitude of the regular visitors to museums and exhibitions. I didn’t want a myth around my work and myself to develop either.

Whenever possible, I highlighted my intentions for change, for which this research occasionally served as a medium.

The role of the intellectual and the artist in society

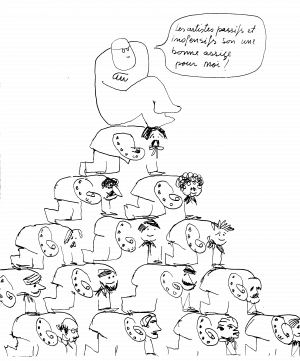

To highlight the contradictions that exist within each milieu. To develop an action such that it is people themselves who bring about change. Nearly all of what is done in the name of ‘culture’ contributes to the conti- nuation of a system based on relationships between the dominant and the dominated. The persistence of such relationships is ensured by maintaining people in a dependent, passive state.

By assimilating new attitudes, society smooths out all the rough edges, transforming anything that might indicate the beginning of aggression towards existing structures into habits and styles.

Today, however, there is an ever-increasing need to question the role of the artist in society. We must acquire greater clarity and increase the number of initiatives; we are in the difficult position of one who – albeit immersed in a given social reality and fully aware of the situation – attempts to take advantage of the available possibilities in order to bring about change.

When people begin to see with their own eyes, when they understand that the mental patterns in which they are trapped are far from their everyday reality, the conditions are ripe for action to destroy these patterns.

Admittedly, the huge weight of the artistic tradition and the way in which it conditions us gives cause for doubt. Several times, we have turned our gaze towards the past, where we find the historical stereotypes and established values that attempt to propagate themselves.

It is easy to see two very different blocs within society. On one hand, there is a minority that totally determines the life of this society (politics, economy, social norms, culture, etc.). On the other, there is an enormous crowd that follows that which the minority has decided. This minority acts in such a way that things continue as they are, and even though appearances may change, the relationships remain the same.

If we position ourselves within this perspective, we can observe two very different attitudes in intellectual and artistic production. On the one hand, everything that – deliberately or otherwise – helps to maintain the structure of existing relationships, to conserve the characteristics of the current situation; on the other hand, scattered all over the place, initiatives that – deliberately or otherwise – try to undermine these relationships, destroy the mental schemas and beha- viours that the minority relies on in order to dominate.

These are the initiatives that we must develop and organize. It is a matter of drawing on professional ability acquired in the field of art, literature, cinema, architecture, etc., and – instead of simply following the path already laid out, that of consolidating the social structures – prefer to call the prerogatives or privileges inherent to our situation into question. It is a matter of awakening the potential ability that people have to participate, to decide for themselves – and to encourage them to make contact with other people to develop a shared action, so that they play a real role in everything that fills their lives.

It is a matter of making people aware that work, whether it is done in the name of culture or art, is only destined for an elite. That the schema through which this production enters into contact with people is the same as the one on which the system of domination depends.

The unilateral determinations in the art field are identical to the unilateral determinations in the social field.

Conventional artistic production is demanding with respect to the spectator. In order for them to appreciate it, special conditions are implied: a degree of knowledge of art history, special information, an artistic sensibility, etc. Those who can meet these requirements obviously belong to a very specific class.

So we are collaborating with a whole social mythology that conditions people’s behaviour. We find the myth of the individual thing, versus the communal thing; the myth of the individual who makes special things, versus the individual who makes communal things; the myth of success, or even worse, the myth of the possibility of success.

Everything that justifies a situation of privilege, an exception, bears within itself the justification of the unprivileged situations of the majority.

This is how, for instance, the myth of the exceptional individual (politician, artist, billionaire, devout, revolu- tionary, dictator, etc.) emerges and spreads, which implies its opposite: individuals who are nothing, the poor, the failures, the ignorant. This myth and several others are mirages that maintain the situation: each individual, at some time or other, is called on to adhere to it, since ‘success’ belongs to the scale of values underpinning these social structures. In our own milieus, we can call the social structure and its extensions into question within each specialty field. We can coordinate everyone’s intentions and create disruptions to the system.

One way or another, we are contributing to the social situation. The problem of people’s dependency and passivity is not a local but a general problem, even if it has various guises. It becomes more acute in centres where tradition and culture have more weight and where the social organization is more evolved.

Young painters who have been conditioned (through teaching, by being immersed in ideals that conform to pre-established patterns, by the illusions of success, etc.) can be stimulated by certain facts and can orient their work in a different direction. They can:

• Stop being unthinking and involuntary accomplices to social regimes in which the relationship is that of the dominant to the dominated.

• Become motors, and awaken people’s dormant capacity to take their destiny into their own hands. • Revive their powerful aggressiveness against the existing structures.

• Instead of seeking innovations within art, change, as much as possible, the basic mechanisms that condition communication.

• Recover the creative capacity of current working artists (generally involuntary accomplices to a social situation that maintains people in a dependent, passive state); attempt to create practical actions to contravene existing values and smash patterns; trigger a collective awareness and clear-sightedly prepare programmes that reveal the potential for action that people carry inside them.

• Organize a sort of cultural guerrilla warfare against the current state of things, highlight contradictions, create situations in which people recover their ability to bring about change.

• Fight against every tendency towards the stable, the durable, and the definitive, everything that increases a state of dependency, apathy, and passivity linked to habits, established criteria, and myths – and other mental patterns born of a conditioning that colludes with the structures in power. Systems of living that, even if we change political regimes, will continue to maintain themselves if we do not call them into question.

Henceforth, what is important is no longer the work of art (with its qualities of expression, content, etc.), but rather confronting the cultural system. What counts is no longer art, but the attitude of the artist.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, March 1968.

At Documenta, we observe once again that the main function of ‘cultural institutions’ resides in the sacrali- zation of art, consequently, mystification and its goal, the commercialization of cultural production.

It is hard for us, as artists, to escape this compromise in the current situation and we are aware of it.

We have therefore decided to definitively withdraw our artworks from Documenta, thus making our symbolic contribution to the collective awareness with a view to cultural revolution.

Enzo Mari, Julio Le Parc, Kassel, 26 June 1968.

What can an artist of my generation do in the current situation? An artist with an ambiguous situation like mine, compromised within the cultural system, and aware of this compromise? An artist like myself, who sees how easily the bourgeoisie assimilates every new thing that art produces? An artist like myself, who, despite having tried to transform the condition of the artist and the work, and their relationship to the viewer, remains clear-sighted with respect to the limited value of these efforts and the contradictions of this process within the art world? What can be done?

I have known for some time that our two-sided situation may correspond to a two-sided attitude. That, although receiving support within the cultural system (recognition, an audience, funding, etc.), it is possible to attempt to break through the rigid structures of the cultural system by creating conditions for the liquida- tion of this system.

This can be done in two ways. The first consists of highlighting the contradictions in the art world, the role of art in society, and our own contradictions. This is done via texts, manifestos, declarations, public debate, exchanges of ideas with other artists, and so on. Above all, the goal is to enlighten future generations, to show them the hidden aspect of art.

The second way involves attempting to transform, as much as possible, art’s essential elements, that is, the artist, his or her work of art, and the relationship between the work and the public. Since 1960, working in these two directions, I have developed an entire set of activities within the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel.

Currently, since the tidal wave of events in May and June in Paris, the conditions are completely different, even if the situation within the art world remains nearly identical to what it was previously. A form of conditioning so long endured cannot be undermined in two months of protests. Habits persist. Painters continue to produce their works, galleries and museums continue to show them, critics to critique them, dealers and collectors to assign a monetary value to them, and the ‘general public’, with good reason, remains as in- different as before. Indifferent and distant from ‘class art’, from art that is consumed – if that – only by the bourgeoisie, from art that reasserts within itself all of the privileges of power, from art that maintains people in a dependent, passive state. Despite everything, the experience of May and June created deeper doubts and has fostered a positive receptivity that may bring about new approaches. As always, it could be a race between the effort to get beyond the current artistic situation and, on the other hand, society’s ability to assimilate, integrate, and take advantage of this effort.

We must continue to carry out (as in May) a genuine devaluation of myths; myths that those in power use to maintain their hegemony. We find these myths within art:

The myth of the unique object, the myth of the one who creates unique objects, the myth of success, or worse – the myth of the possibility of success.

Like ‘democratic‘ or dictatorial political power, art shares the same situation in which a minority makes the decisions on which the majority depends. It intervenes in the creation of mental structures by determining what is good and what is not. Thus, it helps to keep people in their current situation of passivity and dependency, creating distances, categories, norms, and values. Every artist and those associated with the art world are implicated. Most are in the service of the bourgeoisie and the system.

Without the possibility of challenging the conditioning that the art world imposes on us, without the possibility of questioning all of the established values around art, without the possibility of carrying out a struggle, even of limited scope, against the extensions of the social system within art, without the possibility of creating a living relationship with social problems, the attitude of the artist can only be one of unqualified and unthinking support for the system, either that or it is reduced to an individualist activity that is allegedly neutral.

Currently, more than before, the artistic problem cannot be seen as an internal struggle of trends, but rather as a tacit struggle, very nearly declared, between those who, whether consciously or not, hold to the system and seek to preserve and prolong it, and those who, also consciously or not, through their activities and their positions seek to explode the system by seeking openings and changes. This struggle becomes more effective and more radical when we question ourselves. When we question our attitude, our production, our place in society, and thus avoid a split personality that allows for a progressive political position while maintaining individual privileges.

It is exactly this tacit refusal to bring the protest all the way into the artists’ studio – in the case of painters and sculptors who protest against the social system – that gives the illusion of contributing something, while avoiding seeing that we are part of that same system.

What is most effective for profoundly transforming the system as a whole (while also relying on mass movements) is seeking to make profound changes within each domain.

We can no longer hope that change will come about through external forces. Even in the art world, true change can only come from the rank and file, because it is the (socially conditioned) rank and file that, through its behaviour, accepts the system, and it is the rank and file that, by a change in its behaviour, can explode the system.

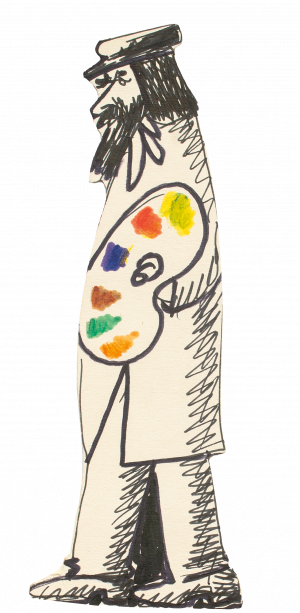

Thus, within the art world, it strikes me as ineffective to attack the cultural system by putting all the blame on something abstract, located who knows where, making it responsible for the state of art today – sometimes it is Malraux, sometimes art dealers, sometimes art critics, sometimes museum directors, but almost never the artists themselves. For example, to protest against the Salon de Paris, one says that the walls of the Musée d’art moderne are disgusting, that there is not enough space, that not enough was done to bring people in, etc. But it is very rare to hear the artists say that salons and exhibitions have no social clout because the basic product (the work of art) is itself without clout; that it is a marginal product, with nearly always a complicit neutrality, or else it wants to be both political and ‘artistic’. It is rare to hear them say that what these salons and exhibitions deserve is the indifference of the public that is its means of defence, or that all the effort that goes into a wider distribution of these cultural products (art in factories, etc.) only serves to maintain people’s mental conditioning by forcing them to again accept the decisions made by a minority. For us, the artists compromised within the system and aware of these problems, there is a task to be accomplished: by acting above all as mavericks, to make young people interested in art aware of the traps laid in the art world. The most urgent task is to question the privilege of individual creation.

This fundamental revolution is the task of future generations, who will have a vision different from ours, and who will be less mentally conditioned and less compromised by the system.

What is there left to do?

Preliminary work: creating the conditions that will make this cultural revolution possible:

• Highlighting the contradictions of the art world. • Creating progressive stages towards change. • Destroying the preconceived concept of the work of art, the artist, and the myths that they give rise to. • Making use of a professional capacity at every occasion when it could call cultural structures into question. • Transforming the pretension of making works of art into a search for transitional means that are able to highlight people’s capacity to take action.

• Turning our attention towards a transformation of the role of the artist, from an individual creator into a sort of activator to bring people out of their dependence and passivity.

• Envisaging, even on a limited scale, collective experi- ments that make use of existing means and that create others – outside of museums, galleries, and so on – not for transmitting ‘culture’, but as detonators for new situations.

• Creating, in a conscious manner, disturbances in the artistic system, using the most representative events. • Campaigning for the creation of groups in other cities with similar intentions and then exchanging experiences.

In this way, a parallel activity can come into being in the art world that, while protesting against it, attempts to have an action based in reality, and that will create the appropriate means on each occasion.

As far as I’m personally concerned, I see my attitude within the art world on three levels:

• 1. Continuing (until new possibilities arise) to make use of the economic means of this society with the minimum of mystification. As a transitional step, multiples may be the appropriate means.

• 2. Continuing to demystify art, and highlighting its contradictions as far as I am personally able, or by joining with other people and groups; by making use of a certain prestige that gives me access to existing means of distribution or by creating new ones.

• 3. Continuing to seek (particularly with others) possi- bilities for creating situations in which the behaviour of the public is an exercise for action.

It is highly possible that these three levels will be interrupted by the development of my activity and that they will present contradictions. But an activity that is based in reality and that seeks to change that reality must take advantage of existing possibilities by creating conditions for a more radical change. This activity can be neither dogmatic nor rigid.

Julio Le Parc, Carboneras, August 1968. Published in French in Opus International.

Several artists who had participated in the actions and running of the FAP, or Front d’artistes plasticiens (Artists’ Front), were asked a series of questions.

The various contributions were published in March 1975 under the title ‘Que se lève l’aube radieuse des artistes’ [May a Radiant Dawn Arise for Artists], in number 7 of the Bulletin paroissial du curé Meslier.

Here is my contribution to this work.

I am taking part in this exercise (one of Father Meslier’s initiatives) in the hope that the confrontation of opinions of the various participants will bring us towards a deeper mutual understanding and then to an actual meeting where the discussion can continue. I also hope that we will be able to draw out the shared fundamental elements likely to further the struggle against the arbitrary in the art world.

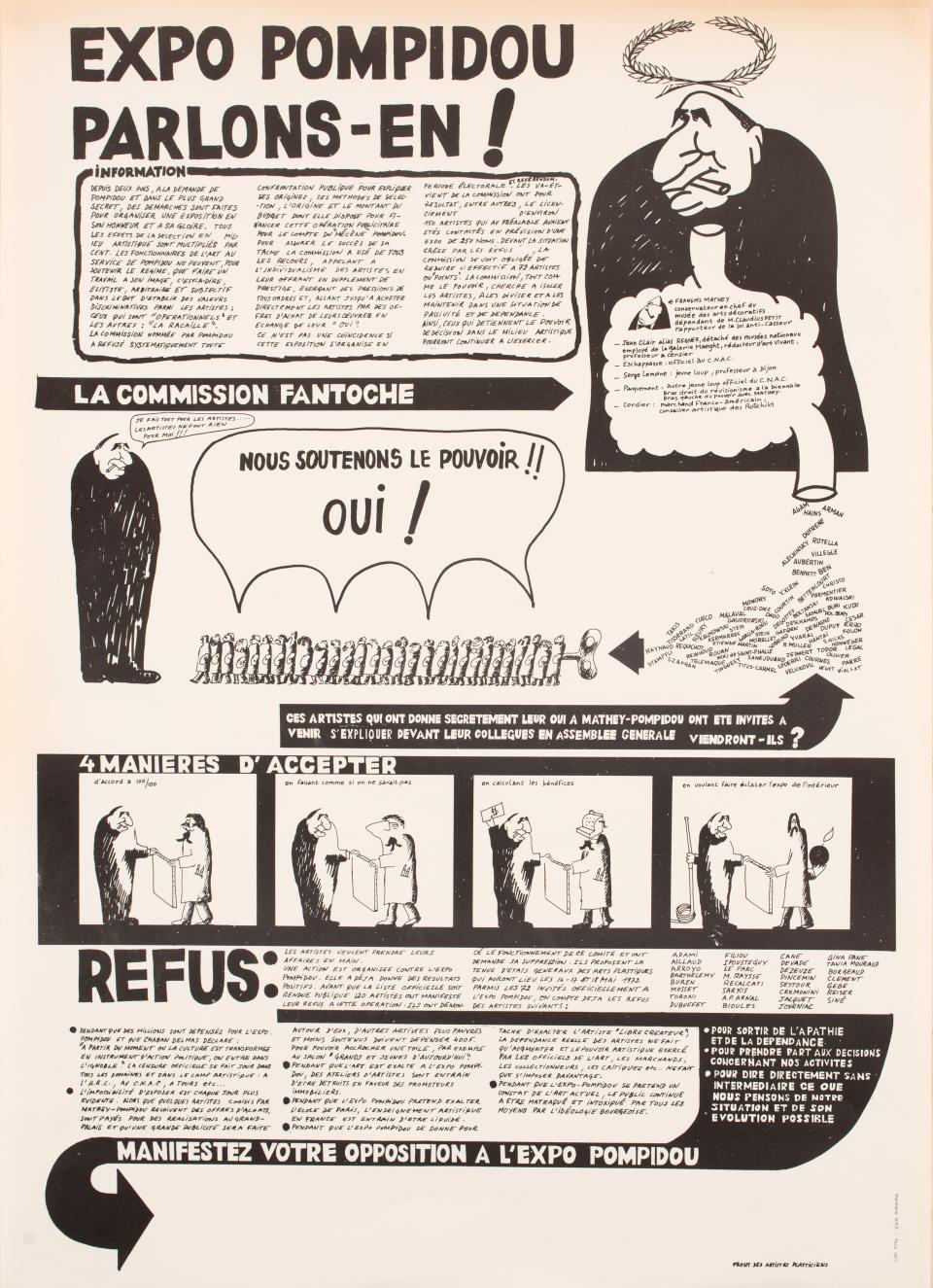

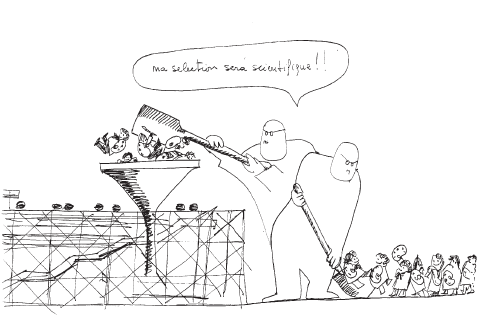

From the beginning I have supported the actions of the FAP, because at the time it was a driving force for artists. It is thanks to this organization that critical issues we face us have been raised. Obviously, its most noteworthy action was the mobilization against the Pompidou exhibition. I was invited to participate indivi- dually and as an ex-member of the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel; I refused to participate in both cases, in support of the artists’ refusal. The FAP’s challenging of the organization of the Pompidou exhibition was positive not only because of the physical, peaceful presence of opponents during the vernissage, which prompted the police crackdown, but also because of the critical analysis made collectively, so that at the time of the vernissage, each artist had taken their stance based on an informed decision. The system of individual solicitation that the exhibition organizers had used was destroyed, because the problem had become collective.

Another important aspect of the task furthered by the FAP was that of the ‘États généraux des artistes plasticiens’ [Assembly of Artists]. This had raised the issue of artists, their work, their relationship with culture, their social relationships, and especially their dependence on those holding power in the art world. Through these assemblies, artists had brought up the question of their relationship with authorities, but the latter had not sought to engage in any dialogue. They retained and still retain their position with its unshared power of decision-making: art critics are critics that in their publications never grant a right of response, salons with their prescriptive commissions make their choices without consulting exhibitors, so-called avant- garde official spaces – e.g., the CNAC (National Centre for Contemporary Art), and ARC (Animation, Research, Confrontation) – develop their exhibition programmes based on the desires of their directors, commercial circuits base their activity on economic profit, the CAVAR continues to track artists, and so on. Even though artists are left in the dark, so too is the public. Official exhibi- tions could be presented behind closed doors, without even seeking the alibi of the public, and with only art critics, dealers, collectors, and officials receiving an invitation, and the result would be the same.

As for initiatives that aim to create a parallel market, they are positive because they bring up the issue of the art market and because they are not seen as an absolute answer applicable to every artist. A different mode of circulation would make more sense if production started heading in a different direction.

We cannot effectively challenge the circulation and marketing of artworks if we cannot challenge artistic production that emerges out of a confrontation between painters about their own works. Every time these types of initiatives have occurred, difficulties have arisen. Generally, artists are not used to coming into confront- ation with the public; we passively await the verdict of art critics, dealers, collectors, art officials, etc.

As for my personal work, I cannot say that I am entirely satisfied with it, but I do it within the current context. It forms part of my individual research. This is my profession, and also the way I earn my living. In a different situation (a socialist society), I could imagine it would be a more interesting task, more collective, open to the masses.

However, this has not prevented me from continually fighting against the mystification that is created around art, both personally and ideally by joining with other painters; this struggle takes different forms – critical analyses of the role of the artist in society, individual or collective research regarding the relationship with the viewer by trying to create a direct connection, without a cultural intermediary and with controllable means, the use of professional services in favour of counter- information and social struggles, and works that are produced as a collective in particular. The most typical examples of these are the Atelier populaire d’affiches in May ’68 and América Latina No Oficial at the Cité Universitaire, which denounced oppression, repression, and torture, and demonstrated the social struggles taking place in Latin America.

The relationship may be questioned between my formal, individual, or collective research and my participation in collective works with figurative images (Salons de la Jeune Peinture) such as: mining, torture, labour, etc. I would reply that no matter how the works may differ, the approach is the same, featuring an exchange of opinions, collective analyses . . .

At the moment, there is not a single recipe for a revolutionary artist that suits everyone. And even productions, behaviour, and actions that are positive in one context may be negative in another. There is no absolute formula for salvation. There are artists who focus their production on political topics, but who do not remove themselves from the circuit of the art market, and who sell their (geometric) paintings at the same price as mine, all the while paying lip service to an art of denunciation, but while remaining isolated, in an individualistic attitude, and who never participate in collective actions against the arbitrary nature of the art world.

Given the dearth of positive initiatives in this milieu, related to these struggles, we cannot favour one to the detriment of the others. We must beware of sterile quarrels. When some groups become particularly demanding, they decrease; it is easy to be intransigent when one is acting on one’s own behalf, but this approach does not mobilize others, and has no effect on the art world. We must consider possibilities and realities.

Seven years after the dissolution of the GRAV, a retrospective exhibition was held in Italy. A book on the GRAV was published on this occasion in 1975. In this book, the former members of the GRAV give their individual responses to questions formulated by Luciano Caramel, the exhibition organizer. Here are the fifteen questions from Caramel and my fifteen answers.

Luciano Caramel: For you, what were the most important reasons that led you, along with the other cofounders, to create the GRAV in 1960?

Julio Le Parc: To break out of isolation, seek permanent debate, share the adventure of research, attempt collective work, and demonstrate that it’s possible to have a different attitude to the one we’ve been conditioned by.

In your opinion, what was your specific contribution to the GRAV’s activity between 1960 and 1968?

My obstinacy to push the Group towards genuinely collective creations by distancing it from the idea that a group equals an addition of personalities.

In terms of your individual work, what were the main consequences of your shared activity within the GRAV?

Owing to debate, owing to a kind of emulation within the Group, I had elements of appreciation that were broader and my individual work had a more active evolution.

What were some, if any, of the most important criticisms that you addressed to the GRAV during its existence? What were some, if any, of the most important discrepancies between your personal position and the Group’s shared position?

The criticism that I addressed to the GRAV during its existence included: not enough collective work, not enough debate, not enough imagination and effort for collective concerns, a lack of boldness, too much fear of risk, too much fear of ridicule, too much respect for conventions, and too much tardiness, quite often being late for events that were transpiring.

What were my differences with the shared positions of the Group? I was supportive, from the outset, of all of the Group’s activities, all of its positions, all of its texts.

What do you now think were the real reasons for the GRAV’s dissolution? What is your view today concerning the dissolution itself and how it took place?

The reasons were given in the act of dissolution and in the texts by four of its members in 1968. In hindsight, the GRAV, prior to its dissolution, had become a dead weight that was out of touch with reality.

Broadly speaking, now, seven years after its dissolution, what is your assessment of the GRAV?

The same as it was at the time of its dissolution.

Beyond superficial evaluations from the critics and art historians, during its existence the GRAV was a positive experience within the social context and cultural milieu (despite its contradictions) and one that has subsequently been extended elsewhere.

By referring to your lived experience within the GRAV, what were, in your opinion, the most positive results of working together? What were the biggest difficulties? And the main limitations?

The most positive results were its written stances (‘Assez de mystifications’ [Enough Mystification, 1961 and 1963], ‘Propositions générales’ [General Proposals, 1961], etc.) and also the collective creations (Labyrinthes, Salles de jeux, Sorties dans la rue, etc.).

The biggest difficulties? Reconciling individual interests with those of the Group and trying to strike a balance between the differences of its members, differences in economic situations, availability, desire for collective work, invention, etc.

Its main limitations? Finding yourself falling within an aesthetic movement and not being able, directly, through expansion, to obtain a foothold within reality.

Nowadays, what do you think of group work in general? Do you consider it desirable? In what way? Within what limits? To what end?

I have always believed in group work and I still do.

Debate is desirable; discussion is desirable; pooling the ability to devise, create, and bring an approach to full fruition collectively is desirable; and above all it is desirable that group work falls within reality with the intention of changing it.

In the current social context and particularly in our milieu, we are not in groups as much as we might like and group work cannot be done individually. The immediate goal, whenever the opportunity presents itself, has been to get away from the individual isolation to which our milieu confines us and in which we can easily be manipulated by those who wield cultural power.

After the dissolution of the GRAV in 1968, what were the prolongations within your activity of the experience you’d had with the GRAV? In particular, have you continued with collective work? Of what sort? With whom?

At the time of the Group’s dissolution, I said: ‘Despite my agreement with its dissolution, I believe more than ever in a collective approach . . .’ In other words, I agreed to dissolve the Group to be able to work in groups. I hadn’t done that exclusively. I’d continued with my individual research. But since the dissolution of the GRAV in 1968 up until the present day, I’ve never stopped participating in collective approaches; either to deepen theoretical analyses, or to undertake shared creations, or to combat the arbitrary elements of the artistic milieu, or in actively supporting the struggle of Latin American peoples, and so on.

It has been seven years now and in this lapse of time, I’ve had more collective experiences than during the GRAV’s eight years of existence. To my deep regret, among these countless collective activities, approaches, and productions (it must be said that in most cases, the participation was anonymous), I have not found my former GRAV companions, except once, but unfortu- nately that time they (four of the ex-members) were on the other side, on the side of power.

Out of all of these experiences, with different motivations and people, I’ve drawn one very useful lesson that encourages me to participate every time a new opportunity for collective work crops up (that is, when the impetus doesn’t come from me).

After the GRAV disbanded, like other former members of the Group, you completely – or at least partly – ceased to be interested in Kinetic Art. Was that simply due to contingencies or was it a shift that, in light of the experiences you and others had had, developed and changed your mind as to the possibilities of movement in visual art?

When a certain amount of our research, distorted by certain art critics, becomes ‘Kinetic Art’ or ‘lumino-kinetic art’ and/or ‘op art’, etc., it’s natural to lose all interest in these classifications. As with all the other aesthetic classifications, they rely on appearances, setting aside the meaning of the approach, its origins, implantation within the artistic milieu, correspondences in the social realm, and extensions. Despite the fact that in some cases, the appearance of my creations (individual or collective) is no different from what they call ‘Kinetic Art’, I feel that they have a very narrow connection in the manner of approaching a problem, analysing its possibilities, situating its variations, drawing conclu- sions, and progressing.

What meaning and goal do you assign to the GRAV era, to the artistic operation per se? In particular, what possibilities and functions do you think it might have within the social context? Today, seven years after the GRAV experience, have your opinions changed? If so, in what ways, predominantly? And, if so, what reasons do you attribute to your change?

Through our intention to demystify art, to decompose its modes of operation, and to theorize our work, we posed quite a few problems. Our starting point was ourselves, since we were conditioned in order to make art, in a certain way and within a given milieu.

At the time, our ideas were refused. Nowadays, they are commonplace and in most cases, devoid of their initial content. They have been developed positively all the same, without needing to assume an aesthetic aspect necessarily. In that sense, and without over- stating our importance, you could say that even in the contradictory situation in which we were debating, the GRAV played a particular role, one that was rather unknown until now.

My opinions as to the GRAV’s role during its existence were useful for setting out a certain number of problems concerning the artist within today’s society, through analyses, attitudes, and artworks.

They haven’t changed. They’ve evolved with new situa- tions, with a militant approach taken within our milieu, non-existent at the time of the GRAV; with a more political and realistic overview of the current situation.

In your opinion, what were the relationships between the GRAV and the constructivist and concretist tradition like? What were the most substantial points of contact? And the most noticeable differences?

Prior to the foundation of the GRAV, the movements called constructivist and concretist were losing speed. It was the reign of informalism, tachisme, lyrical abstractionism, etc. Movements encouraged by the mystification of the milieu (critics, historians, dealers,

art officials, etc.). It had reached such a level of obscurantism and exaggerated proliferation all over the world that for us, the constructivist or concretist movements, with their specific research, struck us as being a base, a point of departure.

Personally, for me the points of contact had been – already in around 1945 in Buenos Aires – the knowledge of the activities and production of the Concrete-Invention Art Group that proclaimed their dialectical materialism and that had raised problems by working with simple geometric shapes and pure colours. Subsequently, the most useful contacts for me were the writings of Mondrian, his œuvre, that of Albers, the knowledge of the black-and-white work of Vasarely, his texts and my personal relationship (though sporadic) with him as well as with Vantongerloo.

The discrepancies came very quickly as soon as we set to work seriously. We criticized, in a constructive way, all of the constructivist artists for not taking the detachment with the artwork produced far enough, for being overly attached to the organization of the surface as a basis for a more or less free composition, and that, in the last instance, with geometric forms, the ‘creator’ behaviour was the same as that of the other artists working with irregular forms.

What were the results of your relationship with the other research groups working in the field of visual art in the 1960s and with the other artists operating within the New Tendency?

The results were positive; the relations were amicable but not always easy. Within the New Tendency, the experience was highly stimulating. There was a recog- nition and mutual and somewhat fraternal affirmation of our existences and our research; which was not the case with the other Kinetic artists in and around 1955 (Agam, Tinguely, Soto, Bury, etc.). We’d tried to take things a step further on the basis of permanent debate and democratic decision-making between the participants of NT. There was no shortage of projects, but we didn’t get any further than the presentation in Paris at the Musée d’art décoratif. The museum was directed at that time (1964) by M. Faré, who let us organize the NT exhibition as we saw fit, which was unheard of at that time.

As with other activities, this event, rather extensive and representative of NT, came too early, within a very Parisian, hostile, and retrograde artistic milieu.

Can you establish a comparison, by highlighting the affinities and discrepancies between the methodological principles of the group’s work concerning the GRAV and those of the other groups operating at the same time?

The most significant affinity, I believe, was with the Gruppo T of Milan, the make-up of which was rather homogeneous and who developed research with new elements (water, air, etc.) by incorporating movement and light. The Gruppo N of Padua was also quite close to us but more attached to the theoretical side. Equipo 57 comprising Spaniards working anonymously in Paris, developed research on surface and volume according to an organizational system characterizing it; the differences with them came from the fact that we gave priority to the visual aspect of our research, relegating the conceptual system to the background a bit, which for us was quite an important basis for control. The group ZERO wasn’t really a working group, the number of its components varied from exhibition to exhibition and, overall, it was more a state of mind that brought them together than shared research.

Do you have any other remarks that seem useful to add, for this first retrospective exhibition of the GRAV?

I agreed with the creation, after its dissolution, of this first ‘historic’ exhibition of the GRAV, provided that the organizers obtained unanimous agreement from the former members. Given that the GRAV no longer exists, a few former members cannot forcibly exhibit those who do not want them to, via the alibi of a historic exhibition of the GRAV, let alone exhibit their artworks and claim to represent the GRAV as a whole. Anyone, even those with flimsy claims to honesty, can understand that. At the time of the GRAV, with the basic majority system, each member weighed in on the decisions and if we didn’t agree with the majority, we could abstain or develop our idea on an individual basis, or, if it came to that, resign. Currently, none of the former members can retrospectively resign from the GRAV. Each one of us can provide our vision of the GRAV but without claiming that it is the only genuine perspective. It is for this reason that I insisted that on this occasion, the brochure prepared by the GRAV about the GRAV in 1968 would form the foundation of this publication. Similarly, I agreed that through this questionnaire, each one of us could now give, seven years after its dissolution, a few personal observations about the GRAV and its problems.

I have one regret: that on the occasion of this exhibition it is not possible – due to opposition from certain quarters – to reconstitute one of the collective experiments of the GRAV and that we remain a sum of individual research paths.

What does Duchamp represent for you today? Does he belong to the past, to the history of art?

Duchamp, along with others, contributed to the foundations of my training as a painter. For me, he did not block out the horizon.

He was there, in books on art, where, as usual, ‘experts’ had done their tidying and had found him a place in the history of modern art. Should I have devoted more time to his works? Should I have left Duchamp and others prisoners within those pages?

Was looking at reproductions sufficient?

In order to understand Duchamp, should I have adapted my gaze by filling my head with those explana- tions and analyses, by this one-upmanship of specialists?

Duchamp questioned the cultural institution by revealing the decisive role of those who have the power to decide what is, or is not, ‘art’ (museum directors, art fair directors, dealers, art critics, collectors, etc.).

Initially he provoked them; for example, by sending a urinal to the New York Society of Independent Artists in 1917. This provocation was then raised to the rank of an ‘artistic act’; and the urinal as an object of art has since been sanctified by the cultural world.

The mystification of Duchamp that took place sixty years ago is still very much alive today.

An act of provocation, if it is not followed up by anything other than individual statements, can easily be assimilated and neutralized by those who wield cultural power.

However, if it is broadened – by breaking down the cultural milieu, by pointing out the various interests of this milieu, by indicating the presence of a dominating power and the manipulation of those dominated, by creating conditions for collective awareness, and by establishing connections with social reality and struggles on various fronts – this act can have true impact, and it can be difficult for upholders of cultural power to appropriate.

Julio Le Parc, October 1976. Reply to Connaissance des Arts.

l have always been inclined to work as a group. When I was a student, l actively participated in advocacy movements and fought against the arbitrary system of teaching; analysing along with my fellow students our education and our situation in relation to modern art, etc. Later, living in Paris, l participated in the formation of the GRAV and in everything that the group did collec- tively. After its dissolution, my belief in collective work did not faIter; on the contrary, it increased. Collective work carried out with different groups varied depending on circumstances, objectives, and modes of execution. In many cases, participation was anonymous.

1. Collective analysis of the current role of the artist, group discussions, public debates, meetings organized among artists such as the one in Havana or those orga- nized by the FAP (Plastic Artists’ Front), etc.

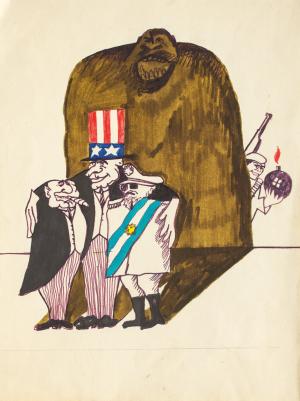

2. Joining the struggle within the cultural environment and mobilizing artists, such as: boycotting the São Paulo Biennial in 1969 when repression in Brazil intensified. ‘No to the Pompidou exhibition’, in 1972, where many artists (regardless of whether or not they had been invited to participate) denounced the manipulation of artists by people holding public offices related to the arts in order to gain prestige for those in power, which culminated in police repression at the failed inauguration of the exhibition, condemning the blackmail carried out by CAVAR (CAVAR is a sort of pension fund that chases artists, forcing them to pay dues, sometimes confiscating their work supplies and giving nothing in return) and occupying official exhibition spaces in order to demand that they be eliminated.

3. Using professional ability, be it in support of local struggles (public poster-making workshop, Secours Rouge des peintres [Painters’ Red Cross]), either to support the grassroots struggles in Latin America (‘Amérique Latine Non Officielle’ demonstration, etc.) through graphic work or by organizing exhibits that condemn oppression, repression, and torture in Latin America. Also, in other cases, using the prestige and recognition of my work.

4. Carrying out collective work such as:

- An experiment developed along with Fromanger and Merri, in which the spectator becomes an artist, through their imagination and the elements placed at their disposal (drawing material, paper, newspapers, magazines, scissors, etc.). Postcards to be sent to public figures, or not, from around the world (Nixon, Mao, girlfriend, professor, son, Pius XII, political prisoners, Cassius Clay, etc.). These images were projected in large format as they were being produced at the game room of my exhibit in Düsseldorf.

- A collective work based on a family album belonging to the widow of a miner who died in an accident, along with 15 other miners, at the bottom of the mine in 1970. As in many other cases, the cause was not a fatality, but rather the demands made for maximum productivity in order to obtain a maximum profit, neglecting the safety conditions of the miners. This collective work included: the photo album printed in offset and another larger one in silkscreen, as well as a group of sixteen paintings. The participants in this collective work were: Aillaud, Arroyo, Biras, Chambaz, Fanti, Fromanger, Gradas, Le Parc, Mathelin, Merri-Jolivet, Pancino, Rancillac, Rieti, Rougemont, Sarrazin, Schlosser, and Spadari. The work was exhibited in Paris in various venues and in the mining region in northern France.

- Several collective works with students from the Fine Arts Department in 1973–74 when l was a visiting lecturer. Some works were done directly on the walls of the Art Department, with themes related to the Art Department’s internal life and to the ongoing struggles at the time. Another piece in two parts, on the subject of work, one part including sixteen black-and-white paintings that traced the vicissitudes of a worker’s life and struggle, and another part with five paintings on the dehumanization of work (hands in white, black, and grey). These works were exhibited in Paris and in other parts of France, notably at the CFTO conference (Workers’ Federal Democracy Confederacy).

- Collective work in 1972 by the Grupo Denuncia (Gamarra, Le Parc, Marcos, Netto) on the subject of ‘Torture’ which included seven paintings in black, white, and grey measuring 2 x 2 metres that were used to support the campaign launched to condemn the use of torture as a method of government in Latin American countries.

- Collective works were carried out by the International Brigade of Painters Against Fascism constituted in 1975 in Venice and made up of: Balmes, Basaglia, Boriani, Eulisse, Cueco, Gamarra, Le Parc, Marcos, Netto, Nuñes, Perusini, Pignon-Ernest, and Van Meel. The three works by the Brigade were: a 12-metre long collective piece in the Port of Venice supporting the dock workers’ boycott of maritime services headed for Chile, which was ruled by Pinochet; a second collective piece in Athens within the framework of the International Congress of Solidarity with Chile; and a third collective work in Paris, 20 metres long, commissioned by the Salvador Allende Resistance Museum.

- Collective works by the Antifascist Painters’ Collective included: At a PSU (Unified Socialist Party) gathering, themed: ‘A world to be destroyed, another to be created,’

we made, in situ, a series of moveable panels that the members of the collective carried around the gathering; the great 10-metre-long banner collectively made in May 1976, based on the Pompidou Art Centre that the members of the collective brought to the May 1st workers’ day parade in Paris. The collective’s members are: Bézard, Bouvier, Brandon, Colin, Counil, Derivery, Dupré, Fromanger, Lazar, Le Cloarec, Le Parc, Matieu, Netto, Perrot, Picart, Riberzani, Vegliante, Vignes, Yvel, and Dego.

AIl of these types of collective works require willing- ness, availability, and a capacity for work that is not always so easy to obtain and this brings up the issue of each person’s relationship to personal research and work.

Collective work in itself does not guarantee excellent results, but within the monotony of the artistic pano- rama, where the struggles among aesthetic tendencies and individual drives to succeed are common, collective work serving a positive purpose is comforting, despite its many deficiencies and difficulties.

A whole series of problems arise through collective work: the relationship between social reality and the reality of carrying out collective work and its insertion into reality. It brings up all the other aspects related to the way one understands collective work, each partici- pants’ share, the system for making decisions, jointly producing, choosing the subject matter, the opportunity to intervene, how the result is used, how it is received, the accomplishment of the objective or lack thereof, etc.

Julio Le Parc, Paris, November 1976.

Questions - 1

Can we go on today with the myth of art as a kind of religion with an elite of initiates; with the myth of freedom of expression, without seeing the narrow limits within which an artist works; with the myth of the artist as super-endowed; with the myth of the work of art as a unique, overvalued product that defies time; with the myth that the public is ignorant, incapable of appreciating the art of its time?

Is it no longer possible to believe in the creative act, resulting from a sudden illumination, a sudden inspi- ration that puts the artist in a trance, so that with his useful messages he conveys imponderables?

Is it possible that the creative act is not just the normal act of looking into one’s self, querying one’s self, but rather a confrontation with daily reality and the social sphere in transformation?

Is it logical, as is often affirmed (not without a degree of cynicism), that artists today should spend fifty percent of their professional time producing their work and the other fifty percent promoting themselves, trying to win over that small nucleus of decision-makers in art?

Is it not possible that the internecine quarrels – without real confrontation – of movements within art are just maintaining artists’ proverbial individualism, pitting some against others, leaving the field open to those who have the power to decide what is or isn’t good in art?

What hides the accelerated succession of fashions in art that elbow one another out?

Should a young artist join art movements’ frantic search for the new, the original at all costs?

From which international centres, via which media, and with what vested interests are the new fashions in art disseminated around the world as though they were slogans? And why are they reproduced locally?

Why does the public opinion exist that contem- porary art, avant-garde art is deceptive, confusing, incomprehensible?

Are new forms of expression, new techniques any guarantee of a new art?

Is it possible that artists as a group are a shapeless, manipulable mass from which the cultural powers- that-be extract, for their own survival, what is useful to them, ignoring the rest?

Can ‘official’ cultural circles go on thinking that artists are such individualistic and obtuse creatures that it is dangerous to incorporate them collectively into the sphere of cultural management?

Is it acceptable for artists today (especially young artists) to find themselves completely dependent on all things related to the diffusion and comparison of their work, whether in private or official exhibition spaces or in the media?

Is it fair that artists always become debtors when they obtain something out of the ‘goodness of the heart’ of the gallerist, collector, museum director, art critic, radio or television broadcaster, etc.?

Can the history of art that is said on a daily basis to be ‘objective’, ‘impartial’, ‘informative’, and without abusive interpretations or valuations be defended?

Who are the people in charge of selection in the art world? What are their criteria? What are their vested interests?

Why is an artist who sells, valued higher, considered better, than one who doesn’t?

Can we accept the criterion used by some art galleries that a good picture is a picture that sells?

Can we accept that in the last instance it’s the person with money who decides what’s good and what’s not in art?

Should artists today aspire to having their work be overvalued by the art market, to having it be worth millions, and to having purchasers confine it to their private living rooms when not in some vault somewhere?

Is it possible that imbued with that attitude, many artists conceive their works with that obsession: make it sellable?

Does a close relationship between official organizers, artists, and the public and other social categories not seem necessary?

Can we not imagine that those new relationships might make possible a different situation for the artwork, for its diffusion, and for the way it is received?

Could we not put into practice other methods of selection for exhibitions, cultural activities, official commissions and purchases, etc., than those used by ‘specialists’, so that a real collective responsibility, shared among all interested parties, might emerge?

Can we imagine a cultural policy that ignores the models radiating out from the international centres,

that is not in competition for international supremacy, that is not influenced by governmental pressures, that cares little for the interests of the art market, that is not sustained solely by the aesthetic judgments of its executors, etc.? That is, a non-elitist cultural policy based on information about contemporary creation that is non-partisan and as objective as possible?

Would a cultural policy implemented in that way not make possible a cultural flowering, assuming that cultural richness is the feverish heterogeneity of many artistic conceptions and tendencies in constant confrontation and in direct relation with the public?

Questions - 2

Can we still say...

• That Ibero-American art is one and indivisible? • That it is the historical art of the pre-Columbian

civilizations?

• That it is the art of today that employs signs taken

from those civilizations?

• That it is the art created by some communities in

artisanal ways?

• That it is the art represented by the aboriginal

peoples?

• That it is the art that manages to be seen

internationally?

• That it is the art that tells the history of the struggles

of the people?

• That it is art that sells well?

• That it is the art that joins a conflict?

• That it is the art that locally reproduces the models

of international trends?

• That it is art that attempts to reflect the industrial,

technological world?

• That it is the art that triumphs abroad?

• That it is the art of the naïve painters?

• That it is art that respects academic rules?

• That it is that art that creates its own avant-garde? • That it is the art that certain indigenous tribes yet to

be discovered in Mato Grosso produce?

• That it is art that upholds established values? • That it is the art that seeks a different form of

communication? • Etc.

It is not easy to outline what lbero-American art is today, and the result will always be partial or imprecise. Is it possible to consider Ibero-American art as some- thing fixed, like a corpse to be dissected and analysed by doctors in a laboratory, at a certain distance and from a neutral point of view?

Though somewhat imprecise, in flux and full of contradictions, Latin American art is what it is: the reflection of the convulsive reality of a continent where oppression, repression, and torture are the dominant systems of government.

Is the reality of current Ibero-American art something abstract, removed from us? Is it not the joint product of the social reality and of what we ourselves have created? We, the artists, art critics and scholars, official or private administrators, etc., that constitute this conference.

Can we shirk this responsibility? Every one of us here today at this meeting has been and continues to be responsible for what Ibero-American art is today. And we are especially responsible for what it will become in the future, since many of those here today hold key positions that control the art world. And it is these key positions that decide the value, make selections, praise certain tendencies, and ignore or condemn others.

Is it false to say that through the administration of artistic activities in our cities, the schemas that are being reproduced are the same as those of the imperialist international centres?

In the big cities of our continent, haven’t we all seen retrograde art administrators defending academia, opposed on principle to anything new; the avant-garde administrators who, while travelling through Europe or to New York, act as a bridgehead for the dissemination of these international centres, creating around themselves a small court of artists to promote, so long as they re- create on the local level the international avant-gardes;

or the most recent phenomenon: administrator-tutors who manipulate artists by creating artificially constituted groups that they use to personally promote themselves internationally, leaping from one -ism to another?

Does this string of -isms that is a product of the critics’ artificial classifications contribute a single positive element? Does it not help keep artists in a position of constant rivalry with their colleagues? Does it not leave the artist to his or her own individualism, vulnerable and likely to be manipulated? Is this not how the artists, one by one, end up coalescing into one unsteady mass from which the expert-administrators will extract those who are the most ‘valuable’? According to what criteria? According to what standards? And are not the acts of selecting, classifying, appraising, buying, acts of power?

Conclusion

The dominant classes are conservative. They locally reproduce the capitalist power frameworks, imitate the life model disseminated by the imperialist centres, impose their own criteria and values, and impede the development of creativity. In almost all Latin American countries, the current regimes fight creativity since it is synonymous with reflection, critique, change, and action. ln order to endure, these regimes alienate the population, keeping it passive and dependent.

With art, in the best case, they accept only that which reflects their situation and helps them maintain power – that is, art that increases passivity and depen- dence, art that exports aesthetically pleasing, harmless models, art that subscribes to the model of supply and demand. They thereby denaturalize creativity and see the artist as someone at their service, who can be alienated like the rest of the people.

Perhaps one might say that the true Latin American spirit in art is authentic creation, accompanied by an attitude in keeping with that. This creative attitude in art would parallel the creativity of the people, who, though alienated, continuously invent new ways of fighting against repression, in order to destroy the oppressors and create new modes of coexistence. It would be a creative attitude in art that would help in one way or another to survive or live, help break mental boxes and constraints, eliminate ideological conditioning, passivity, submissiveness, fear, and allow us to understand the possibility of a different future.

Julio Le Parc (conscious of his contradictions as an experimental artist in a capitalist society).

Presentation given at the First Ibero American Meeting of Art Critics and Visual Artists. Caracas, June 1978.

This text was presented at the Rencontres d’Intel- lectuels pour la souveraineté des peuples de notre Amérique [Meeting of Intellectuals for the Sovereignty of the Peoples of Our America], Casa de las Americas, Havana, September 1981.

Latin America is a continent that fights simultaneously against the political, economic, and military penetration of American imperialism and against its desire to use culture as a weapon for domination.

Former strategies inherited from Old Europe for im- plementing cultural systems have regained their power here, and means of mass communication, aided by the acceleration of communication in general, have proven to be the ideal instrument to directly or surreptitiously propagate the imperialist ideology and way of life. In the field I work in, that of visual arts, one can clearly observe how successfully imperialism has managed to control all the international bodies that attribute value, ensuring that the works created by its artists (overpriced) are permanently at the fore.

With regard to visual arts in our Western world today, one cannot apply a rigid policy of protectionism at a national level, such as occurs with other products, because artistic products from other international centres do not necessarily require a physical presence: innovation only needs to cross borders in the form of information for the local cultural system, which is based on those international centres, to adopt them through imitation. It does not matter whether these products are good or not. Insofar as artists from across the globe develop an authentic investigatory and creative form of research, while respecting the parameters of visual arts, their contribution is perfectly valid. What is not acceptable is the way in which this contribution is used and manipulated – the artificial and exclusive creation of value by those in power who are responsible for deve- loping the art world at a local and international level.

I believe that isolation, and therefore the ignorance of what happens in the rest of the world, is neither desi- rable nor possible for arts in Latin American countries; an isolationism focused on the past in the search for a hypothetical national identity; an isolationism that while preserving its current system of selection and value-creation adds to its own criteria, detached from local reality; an isolationism that chauvinistically exalts all that is national according to the interests of the dominant class; a retrograde isolationism that harks back to an old form of academicism. An isolationism that rejects international confrontation would also reject internal confrontation.

During meetings with groups of young artists from several Latin American towns, I observed a justifiable mistrust towards the art of international centres. I pointed out, however, that in these centres, young artists like them are continually fighting against a hostile environment where, apart from the private market, the circulation of art is controlled by technocrats who are mostly deaf to, insensitive to, and unfamiliar with their problems. Although it is obviously important to resist the cultural penetration that brings these innovations and standards of value, we must also make contact with all those around the world who try, in one way or another, to bring about the conditions for a different situation for artists.

We cannot look at the issue of Latin American art in aesthetic terms. Today, in good times and bad, we must support the diversity of movements. Many move- ments exist in Latin America, applied with more or less authenticity. It is risky and arbitrary to qualify some as progressive or revolutionary and others as being retrograde and in service to the dominant class.

In itself, artistic creation does not have an intrinsic value that resists time and extends across all latitudes.

But the problem is that there are people who have decided that their standards of value are universal and indisputable. In addition, some works or artistic move- ments that for the moment can be qualified as positive have been considered and classified by the dominant class for the most superficial of reasons and inscribed in the ‘contemporary history of art’ for all these poor reasons; their contribution and all that goes against the interests of the dominant class are neutralized. Thus devitalized, these artistic works or movements end up forming part of the exclusive heritage of the dominant class that dictates its own standards of appreciation and indicates to the public the position it must take in relation to them.

It is no coincidence that the attitude of the public towards these works is almost always one of inferiority, passivity, and dependence; they further accentuate the public’s submission to the established order, inhibit its personal judgement, and deaden its natural creativity, isolating it in individual contemplation and thus remo- ving any possibility of intervening in what is presented as Art with a capital ‘A’ and what is completely foreign.

This way of manipulating the artistic world can be observed in all manifestations of culture and with even more conclusive results in sectors other than the visual arts, for example, the press, radio, cinema, or television. These means of communication are no longer only used to slow down people’s natural impulses for developing their personalities, but, skilfully handled, they have been converted into privileged channels for mental penetra- tion that promote an attitude of resignation towards the injustices of this world, presented as inevitable and natural. They thus inculcate the almost inaccessible way of life of the local dominant classes, which is simply the reflection of the way of life of dominant classes at an international level.

The correlation between the general system of op- pression used at an international level and that applied locally is obvious. This same correlation exists in the field of art and culture.

Although it has been repeated a thousand times, it is worth pointing out the case in general; this allows us to identify the means more precisely and to resist the situation by establishing a register of all that is done in this direction. For example, alongside the television or film producer who develops a seemingly innocuous product in service to the dominant class’s ideology, there are people in this profession who, in spite of the rigid mechanisms of operation of these media, try to introduce into their creative work elements of reflection intended to awaken the viewer’s sense of critical thinking, thus preparing the way for more radical changes in society.

This is the same for visual arts. Throughout the world in recent years, a multitude of attitudes, behaviours, achievements, and combats have been observed, all seeking a new vision of artistic know-how. Just as there is a top-down internationalization of standards of value and of value-creation by imperialist centres, there should be an international organization that unites producers from all countries and that fights against the arbitrariness of the world of the visual arts and against the hegemony of the United States. The participation in this fight of Latin American artists, inside and outside Latin America, is important.

Now we must set up an analytical register of all that has been done to this end. Making these experiments known, with both their successes and their errors, is probably much more useful for a rising generation of artists than the innumerable books on the avant-garde based on ‘aesthetic’ criteria and meeting international standards of value.

In my opinion, the current situation of visual arts is a chain in which the producer and product, those who circulate and what is circulated, and those who consume and what is consumed can be found. The key point of this chain is ‘value-creation’. This value-creation lies in the hands of a small number of people responsible for separating the wheat from the chaff in art and for circulating what they choose; the selected work takes on all its social reality through the act of purchase by the collector or through the sacralization granted by art officials in art’s privileged places: salons, international exhibitions, public spaces, museums, etc. Members of the public are excluded from all this (their entry into certain museums barely counts), regarded in the best of cases as well-intentioned but impotent amateurs, carrying no weight in the history of visual arts. They are suspected of being uncultivated people who only like ‘easy’ paintings and who make fun of avant-garde art or who are quite simply unaware of it, generally regarding it as hostile and incomprehensible, far from daily concerns.

Just as value-creation at an international level determines aesthetic tastes at a global level according to the evolution of artistic fashions, at the local level, value-creation by the minority determines what is done locally, in a more or less equally submissive way depending on the degree to which it imitates interna- tional criteria. However, it is precisely here that we can create a space in this closed system that excludes the creation of any value other than its own.

We can propose an infinite variety of initiatives and require their practical application (using state funds in particular) in order to develop different cultural policies through a broad confrontational approach that would allow multiple values and provide new foundations for artistic creation.

Creation, like all aspects of social life, must be a shared concern and must not be delegated to a small group, whether in regard to acts of creativity, value- creation, or social integration. In societies that have adopted the capitalist system, it is absolutely necessary to break down the mythical individualism of artists so that as part of a group they can reflect on the role that they play in society, on the system of creation, value-creation, circulation, and the social function of their work. They will thus make a collective impact on their own milieu and will be able to denounce what seems arbitrary, adopt behaviours suitable for trans- forming the cultural system, join with progressive groups from other disciplines, and coordinate their efforts towards change.

Thus, during activities as commonplace as salons, acquisitions, public commissions, national selections, official exhibitions, and so on, the direct participation of artists, critics, art specialists, officials, and the public in general could be required, by way of a system of value-creation and multiple selections in continual confrontation, which would leave its mark through a constant exchange of opinions, thoughts, constructive criticisms, and open dialogue. All this would set up fresh criteria for the appreciation of artistic creation, establish shared responsibilities, and create new relationships between all those who are concerned with art. This is the only way that creation, in its new form, can be conveyed to the common people.

It would initially be a question of no longer regarding the viewer as a passive being, dependant, and of no importance, but instead as a living being in a reality about to be transformed, somebody able to observe, reflect, compare, and act, a social being capable of forging an opinion together with other protagonists, understanding the problems, and finding solutions.

Out of this, the foundation for a Latin American identity will emerge. This cannot be decided by decree, or by academic paths, or even by the revolutionary avant-garde. Latin American cultural identity is a task belonging to the present and the future. This issue is relevant for everyone, as the enormous creative capaci- ties of the Latin American people could be developed in every domain, a people that neither the most atrocious dictatorships nor the oppression of imperialism have yet managed to destroy. This cultural identity exists impli- citly and takes into account all that has been done and all that has helped, in one way or another, to preserve the people’s aspirations for another way of living life as a society and another way of life in general, in this, our Latin America.

To end my presentation, I would like to propose some concrete measures including the reaffirmation and generalization of what has already been done and what continues to be done every day in the field of visual arts, and which contributes modestly to the daily efforts of the true Latin American in his or her fight. Let us note in particular:

• The many stances against social injustice, support for humanitarian causes, defence of human rights, and solidarity with the justified aspirations of the people;

• Specific attitudes vis-à-vis what is arbitrary in our cultural milieu and of behaviours designed to change the system that governs how the visual arts operate;

• The use of professional capacities in the service of precise causes related to fights belonging to the people;

• Serious, investigative, and creative research within the parameters of the visual arts;

• Open attitudes leading to interdisciplinary and collective work, related to social realities.

And to conclude, I will make a more concrete proposal to the Casa de las Americas, which, I believe, will be in agreement with the idea of creating a broad Latin American front of intellectuals and artists. The Casa de las Americas has been and remains a centre for vibrant cultural activity, a place for meetings, exchanges, and achievements that have given a new shape to Latin American cultural life. Its value and importance for Latin American creators and the circulation of their works has been illustrated many times over.

There are many of us who wish to see more Houses of the Americas on our continent and even in Europe. We see it as the ideal instrument for circulating Latin American creations. This initiative would make it possible to develop and intensify mutual knowledge of what is done in many creative fields. With regard to Europe, it could help us reinforce links with the dynamic aspects of European culture. Even if that may appear utopian, imagine the creative output of all these Houses of Americas. I would propose, as a starting point within the Cuban Casa de las Americas, the training of a broad committee made up of creators from various disciplines, Latin American or otherwise, whose functions and com- position remain to be determined.

In addition to being officially invested, due to their training, with representation in the Casa de las Americas, the members of this committee would coordinate all local initiatives, combining their efforts to create, if not many local Houses of Americas, at least one centre of activities in the spirit of the Casa de las Americas. At the same time, they could be responsible for transmitting to the parent organization all the suggestions, initiatives, ideas, criticisms, and contributions from local creators, putting them forward for the approval of the com- mittee. We could thus develop a closer relationship of shared responsibility, and creators from many countries would benefit from a space for direct intervention. This committee could hold periodic meetings, obviously in the Casa de las Americas in Havana, but also in other countries, to diversify relationships with local creators and relevant institutions, which could in turn lead to shared initiatives.

This work would gradually consolidate new attitudes and behaviours, which themselves could be used as a basis for exchange and for the conditions necessary to the production, circulation, and added value of Latin American creations. All this would make the develop- ment of solidarity with different peoples possible, giving rise to a broad front of Latin American culture against imperialism.

Julio Le Parc, Carboneras, August 1981.